Drug Eruptions

Comprehensive guide to drug eruptions: causes, diagnosis, management, and severe reactions in dermatological emergencies.

Drug eruptions represent a significant category of dermatological emergencies, manifesting as adverse cutaneous reactions to medications. These reactions vary from mild, self-limiting rashes to severe, life-threatening conditions requiring immediate intervention. Understanding their clinical presentations, implicated drugs, and management is crucial for clinicians in emergency settings.

What are drug eruptions?

Drug eruptions, also known as drug rashes or cutaneous adverse drug reactions (CADRs), are skin manifestations triggered by systemic drug administration. They encompass a spectrum of reactions, with most being mild and resolving upon drug discontinuation. However, severe forms can involve multi-organ damage, necessitating urgent care.

The incidence of drug eruptions is estimated at 2-3% in hospitalized patients, with higher rates in those with polypharmacy or underlying conditions like HIV. Antibiotics, anticonvulsants, and NSAIDs are frequent culprits.

Who gets drug eruptions?

Any individual exposed to medications can develop a drug eruption, but certain populations are at elevated risk. These include patients with a history of atopy, HIV infection (up to 10-fold increased risk for severe reactions), and genetic predispositions such as HLA-B*5701 for abacavir hypersensitivity.

- Immunocompromised patients (e.g., HIV, transplant recipients)

- Individuals with prior drug allergies

- Elderly patients on multiple medications

- Children receiving antibiotics

Severe eruptions like Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) show genetic associations, particularly with sulfonamides in certain ethnic groups.

Clinical features

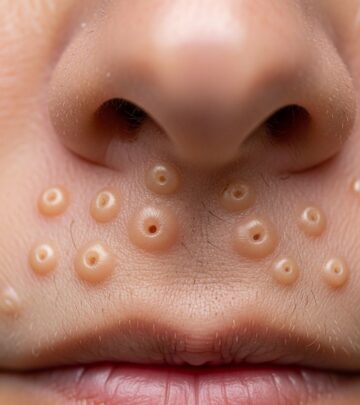

Drug eruptions exhibit diverse morphologies, often mimicking other dermatoses. The latency period typically ranges from days to weeks after drug initiation, though immediate reactions (e.g., anaphylaxis) can occur.

Common patterns

- Morbilliform (exanthematous): Most frequent (90% of cases), resembling measles with maculopapular rash starting on trunk, spreading to extremities. Often pruritic, resolves in 1-2 weeks.

- Urticarial: Hive-like wheals, intensely itchy, migratory. Common with penicillins, NSAIDs.

- Fixed drug eruption: Recurrent oval patches at the same site upon re-exposure, often involving lips/genitals. Caused by NSAIDs, tetracyclines.

Severe patterns

- Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): Widespread pustules on erythematous base, fever, eosinophilia. Antibiotics like beta-lactams implicated.

- Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): Diffuse rash, facial edema, lymphadenopathy, organ involvement (liver, kidney). Anticonvulsants common.

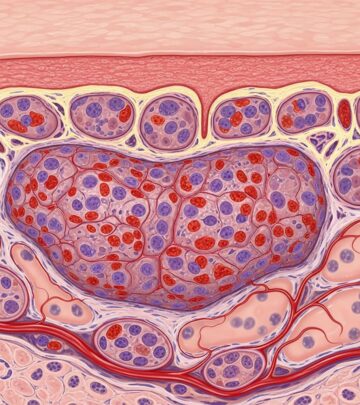

Skin biopsy may reveal interface dermatitis, eosinophilic infiltrates, or necrotic keratinocytes depending on type.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis relies on clinical history, temporal association with drug exposure, and exclusion of mimics (viral exanthems, infections). Key steps include:

- Detailed drug history: All prescriptions, OTC, herbals, supplements in past 8 weeks.

- Physical exam: Rash distribution, mucosal involvement, Nikolsky sign (for SJS/TEN).

- Laboratory: CBC (eosinophilia), LFTs, RFTs for systemic involvement.

Patch testing or intradermal tests post-resolution for select cases (e.g., AGEP). Biopsy confirms patterns like lichenoid or spongiotic dermatitis.

| Diagnostic Tool | Indications | Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Drug history | All suspected cases | Identifies culprit (e.g., new antibiotic) |

| Skin biopsy | Atypical/severe presentations | Histology supports diagnosis (e.g., full-thickness necrosis in TEN) |

| Patch testing | After rash resolution | Confirms hypersensitivity (read at 48-120h) |

Differential diagnosis

Drug eruptions mimic infections, autoimmune diseases, and malignancies. Key differentials:

- Viral exanthems (e.g., measles-like from EBV + ampicillin)

- Bacterial infections (scarlatiniform rash)

- Autoimmune: Erythema multiforme, vasculitis

- Photodermatitis: Sun-exposed distribution

SJS/TEN differentials include staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), which spares mucosa and has superficial split.

Investigations

Beyond history and biopsy:

- Blood tests: Eosinophilia suggests hypersensitivity; viral serology if infectious mimic suspected.

- Imaging: Rarely, for systemic DRESS (e.g., chest X-ray for lymphadenopathy).

- Patch testing: Gold standard for delayed hypersensitivity, performed 1 month post-resolution.

Management

Cornerstone is prompt drug cessation. Supportive care tailored to severity:

Mild eruptions

- Symptomatic: Topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, emollients.

- Monitor for resolution (7-14 days).

Severe eruptions (SJS/TEN, DRESS)

- Admit to burn ICU: Fluid/electrolyte management, wound care, infection prevention.

- Immunomodulators: IVIG (controversial), cyclosporine, corticosteroids (weigh risks).

- Nutritional support, pain control.

Avoid re-challenge with culprit or cross-reactive drugs. Desensitization for essential meds (e.g., chemotherapy).

Severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs)

SCARs include SJS/TEN, DRESS, AGEP with mortality up to 30% for TEN. Risk factors: HLA alleles, slow acetylator status. Management emphasizes supportive care over specific therapies.

Drug-induced anaphylaxis and serum sickness

Anaphylaxis: IgE-mediated, immediate (minutes-hours). Features: Urticaria, angioedema, hypotension, respiratory distress. Epinephrine first-line.

Serum sickness: Type III hypersensitivity, 1-3 weeks post-exposure. Fever, arthralgias, urticarial rash, lymphadenopathy. Resolves with steroids.

Complications

- Secondary infection, scarring (especially SJS/TEN).

- Chronic sequelae: Ocular scarring, nail dystrophy, GI strictures.

- Multi-organ failure in DRESS/TEN.

Prevention

Screen high-risk patients (e.g., HLA testing for carbamazepine in Asians). Patient education on allergy documentation, medic-alert bracelets. Pharmacovigilance reporting.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: How soon after starting a drug does a rash appear?

A: Typically 1-2 weeks for morbilliform, immediate for IgE-mediated, up to 8 weeks for severe types.

Q: Can over-the-counter drugs cause eruptions?

A: Yes, NSAIDs like ibuprofen and supplements frequently implicated.

Q: Is patch testing safe after a severe reaction?

A: Generally performed post-resolution under specialist supervision to avoid re-activation.

Q: What is the prognosis for SJS/TEN?

A: Mortality 5-10% for SJS, 20-40% for TEN; long-term morbidity common.

Q: Should I stop my medication if I get a rash?

A: Consult a doctor immediately; do not self-discontinue critical meds without advice.

References

- Drug eruption – Wikipedia — Wikipedia contributors. 2023-10-15. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_eruption

- Drug Rashes: 7 Medications That Can Cause Skin Reactions — GoodRx. 2024-05-20. https://www.goodrx.com/health-topic/dermatology/drug-rash-skin-reaction

- What is a Drug Eruption? — Contour Dermatology. 2023-08-12. https://contourderm.com/drug-eruption/

- Drug Eruptions and Reactions — Merck Manual Professional Edition. 2025-01-10. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/dermatologic-disorders/hypersensitivity-and-reactive-skin-disorders/drug-eruptions-and-reactions

- Cutaneous Adverse Drug Reaction — NCBI Bookshelf, StatPearls. 2024-07-05. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK533000/

Read full bio of medha deb