Female Pelvic Anatomy: Structure and Function

Understanding the female pelvis: anatomy, structures, and their vital functions.

Female Pelvic Anatomy: Understanding the Structures and Functions

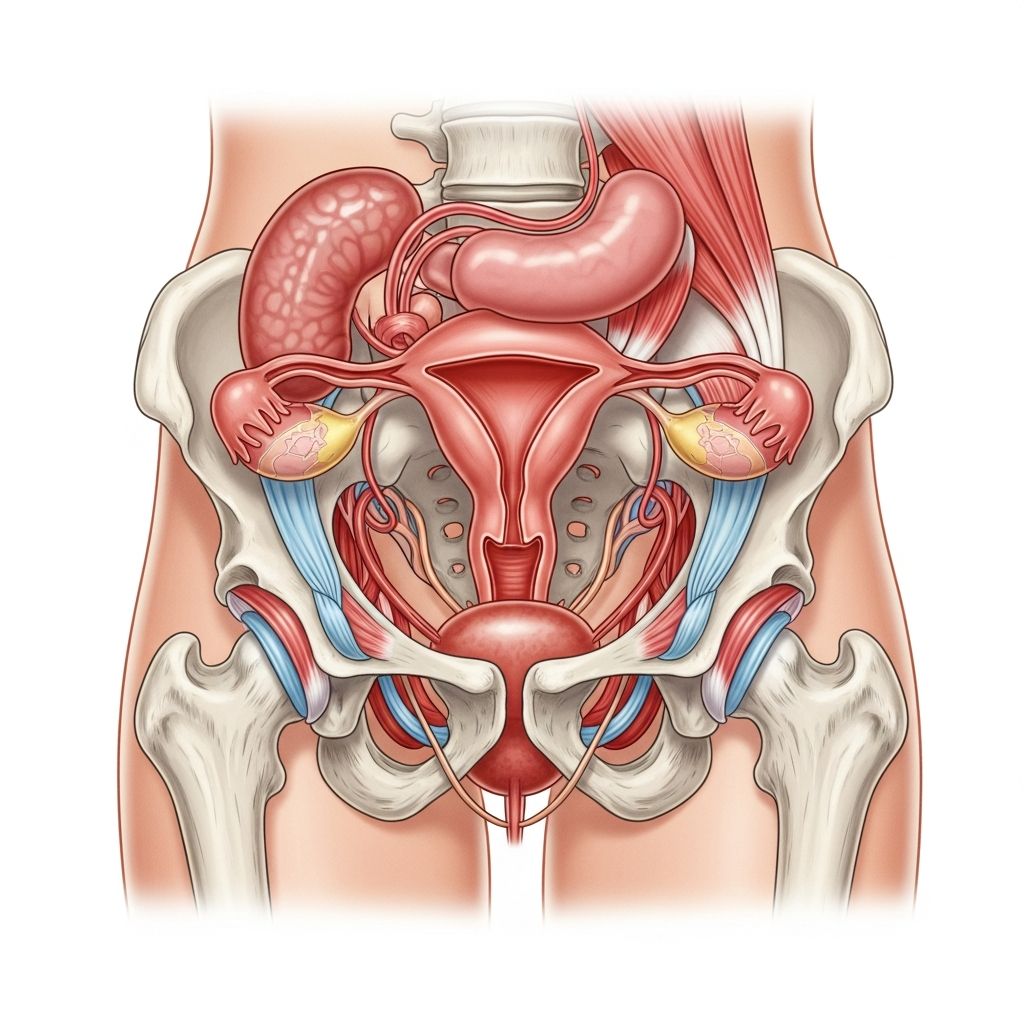

The female pelvis is a complex anatomical structure that houses and protects vital reproductive and urinary organs. Understanding the anatomy of the female pelvic area is essential for women’s health, as it helps individuals recognize normal variations, understand medical conditions, and make informed decisions about their healthcare. This comprehensive guide explores the key structures, their functions, and their interconnections.

Overview of the Female Pelvis

The female pelvis is a bony framework formed by the sacrum, coccyx, and two hip bones (innominate bones). Unlike the male pelvis, which is narrower and more heart-shaped, the female pelvis is wider and more circular, allowing space for pregnancy and childbirth. The pelvic cavity is divided into two regions: the greater pelvis (false pelvis) above the pelvic inlet, and the lesser pelvis (true pelvis) below.

The female pelvic structure creates an environment where numerous organs coexist in a relatively compact space. These organs include reproductive structures, parts of the urinary system, and portions of the intestines. The pelvis is supported by layers of muscles and connective tissue that maintain organ position and function.

Reproductive Organs

The Uterus

The uterus is a muscular, pear-shaped organ located in the central lower abdomen. It is approximately 7-8 centimeters long and is divided into three main sections: the fundus (top), the body (main portion), and the cervix (lower part). The uterine wall consists of three layers: the perimetrium (outer layer), the myometrium (thick muscular layer), and the endometrium (inner lining that sheds during menstruation).

The uterus is held in place by several ligaments, including the uterosacral ligaments, which extend from the uterus to the sacrum, and the cardinal ligaments, which provide lateral support and contain blood vessels and nerves. These ligaments are crucial for maintaining proper organ positioning and preventing prolapse.

The Fallopian Tubes

The fallopian tubes, also called oviducts, are slender tubes approximately 10-12 centimeters long that extend from the uterus toward each ovary. Each tube is divided into four sections: the intramural portion (within the uterine wall), the isthmus, the ampulla, and the infundibulum (funnel-shaped end). The fimbriae are finger-like projections at the end of the fallopian tube that help guide the released egg toward the tube during ovulation.

The fallopian tubes are lined with ciliated epithelial cells that create a wave-like motion to move the egg toward the uterus. Fertilization typically occurs in the ampulla of the fallopian tube.

The Ovaries

The ovaries are almond-shaped organs, each approximately 3-4 centimeters long, located on either side of the uterus. They are held in place by the ovarian ligament medially and the infundibulopelvic ligament laterally. The ovaries serve two primary functions: producing eggs (ova) and secreting hormones, including estrogen and progesterone.

The ovarian surface is covered with a germinal epithelium, beneath which lies the stroma containing follicles at various stages of development. During the reproductive years, the ovaries undergo cyclic changes, releasing a mature egg during ovulation approximately every 28 days.

The Vagina and External Genitalia

The vagina is a muscular, elastic canal that extends from the cervix to the external genitalia. It is lined with stratified squamous epithelium that provides protection and accommodates changes during sexual intercourse and childbirth. The vaginal wall is supported by the pubococcygeus muscle fibers and is strongly anchored to the pelvic sidewall through the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, which are critical for preventing vaginal wall herniation and maintaining continence.

The external genitalia, collectively called the vulva, include the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, and vaginal vestibule. The clitoris contains numerous nerve endings and is highly sensitive, playing an important role in sexual pleasure.

The Urinary System

The Bladder

The female urinary bladder is situated on the intrapelvic surface of the anterior vaginal wall, firmly anchored to the distal vagina by the urogenital diaphragm. The bladder is a hollow, muscular organ that stores urine. When empty, it is relatively small, but it can expand significantly as it fills. The bladder wall consists of three layers: the mucosa (inner lining), the muscularis (muscle layer), and the serosa (outer layer).

The lateral bladder wall derives its support from anterior vaginal wall attachments to the pelvic sidewall. Proper support from these structures is essential for maintaining bladder function and preventing prolapse or herniation with accompanying secondary posterior bladder descent.

The Urethra

The female urethra is a short tube, approximately 4 centimeters long, that carries urine from the bladder to the outside of the body. The anterior surface of the proximal urethra is firmly anchored to the posterior aspect of the symphysis pubis by the pubourethral ligaments and to the remaining distal vagina by the lower two-thirds of the urogenital diaphragm.

The urethra is surrounded by the urethral sphincter, a muscular structure that controls the flow of urine. Unlike the male urethra, which serves a dual purpose, the female urethra is solely involved in urination. The shortness of the female urethra has clinical significance, as it can make women more susceptible to urinary tract infections.

The Pelvic Floor and Supporting Structures

The Pelvic Floor Muscles

The pelvic floor is a complex system of muscles, ligaments, and connective tissue that supports the pelvic organs and maintains their proper position and function. The main muscular component is the levator ani muscle group, which consists of three parts: the pubococcygeus, the iliococcygeus, and the ischiococcygeus. The anterior vaginal wall is strongly supported by pubococcygeus muscle fibers inserting on the vaginal wall and the genital hiatus.

The pelvic floor muscles have several important functions: they support the weight of the pelvic organs, contribute to urinary and fecal continence, provide stability during physical activity, and play a role in sexual sensation and function. Weakness or injury to these muscles may contribute to the development of stress incontinence and other pelvic floor disorders.

Connective Tissue Support

Beyond muscles, the pelvic organs are supported by various ligaments and fascial layers. The cardinal ligaments are particularly important, as they contain blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels that supply the uterus and upper vagina. The uterosacral ligaments extend posteriorly and provide additional support, particularly helping to maintain the anteverted position of the uterus. The pubourethral ligaments anchor the urethra to the pubic bone, essential for maintaining urethral position during activities that increase abdominal pressure.

Blood Supply and Innervation

Arterial Supply

The female pelvic organs receive blood supply from multiple arterial sources. The uterus is primarily supplied by the uterine artery, which arises from the internal iliac artery. The ovaries receive blood from the ovarian arteries, which originate directly from the abdominal aorta. The vagina receives blood from the vaginal artery and vaginal branches of the internal pudendal artery. The bladder is supplied by the superior and inferior vesical arteries, branches of the internal iliac artery.

Venous Drainage and Lymphatics

Venous drainage from the pelvic organs generally follows the arterial supply, with blood returning to the internal iliac veins and ultimately to the inferior vena cava. Lymphatic drainage from the uterus and upper vagina typically flows to the internal iliac nodes, while lower vaginal drainage proceeds to the superficial inguinal nodes. Understanding lymphatic drainage is important for assessing the spread of infections and malignancies.

Nerve Supply

The pelvic organs are innervated by both somatic and autonomic nervous systems. The pudendal nerve provides somatic innervation to the external genitalia and pelvic floor muscles, playing a crucial role in sensation and motor control. Autonomic innervation via the pelvic plexus regulates organ function including uterine contractions, bladder filling and emptying, and sexual responses.

Peritoneal Relations

The pelvic peritoneum is the membrane lining the pelvic cavity that covers certain organs while leaving others covered only on their anterior and lateral surfaces. The uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries are covered by peritoneum, which forms various peritoneal folds and pouches. The pouch of Douglas (rectouterine pouch) is a peritoneal space between the uterus and rectum that is the deepest part of the peritoneal cavity in females. This anatomical feature has clinical significance for various gynecological procedures and conditions.

Changes Throughout the Life Cycle

Adolescence

During puberty, the pelvic organs undergo significant growth and development. The uterus increases in size, the ovaries begin regular cyclic activity, and the external genitalia mature. The pelvic bones also expand to achieve their adult female configuration.

Reproductive Years

During the reproductive years, the pelvic organs undergo regular cyclic changes related to the menstrual cycle. The endometrium thickens and then sheds, the ovaries release eggs, and hormone levels fluctuate. These changes are regulated by complex interactions between the pituitary gland, ovaries, and uterus.

Pregnancy and Childbirth

Pregnancy causes dramatic changes in pelvic anatomy. The uterus expands enormously to accommodate the growing fetus, displacing other organs. The pelvic ligaments stretch and relax due to hormonal changes. During childbirth, the pelvic floor muscles undergo tremendous stretching, and the pelvic outlet expands to allow passage of the baby.

Menopause and Beyond

After menopause, the ovaries cease hormone production, leading to atrophy of the reproductive organs. The vaginal epithelium becomes thinner and drier. The pelvic floor muscles may weaken over time, potentially contributing to incontinence or prolapse if not maintained through exercise.

Common Anatomical Variations

It is important to recognize that pelvic anatomy varies among individuals. The uterus may be anteverted (tilted forward), retroverted (tilted backward), or in a neutral position—all are normal variations. Some women may have a bicornuate uterus (heart-shaped with two horns) or other congenital variations. These variations are typically clinically insignificant unless they cause symptoms or complications.

Clinical Significance

Understanding female pelvic anatomy is essential for recognizing and managing various conditions. Pelvic floor dysfunction can lead to urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, pelvic pain, and sexual dysfunction. Pelvic organ prolapse occurs when weakened support allows organs to herniate into the vaginal canal. Proper anatomical knowledge helps healthcare providers diagnose conditions accurately and recommend appropriate treatments, from pelvic floor physical therapy to surgical interventions when necessary.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the normal position of the uterus?

A: While the most common position is anteverted (tilted forward), the uterus can also be retroverted (tilted backward) or in a neutral position. All three are considered normal anatomical variations and typically do not affect fertility or function.

Q: How important are the pelvic floor muscles?

A: The pelvic floor muscles are crucial for supporting pelvic organs, maintaining continence, and sexual function. Strengthening these muscles through pelvic floor exercises can prevent or treat various conditions including incontinence and pelvic pain.

Q: What is the pouch of Douglas?

A: The pouch of Douglas (rectouterine pouch) is the deepest peritoneal space in the female pelvis, located between the uterus and rectum. It is clinically significant for gynecological procedures and can be a site where fluid or pathology may accumulate.

Q: Why are women more prone to urinary tract infections than men?

A: The female urethra is much shorter (approximately 4 centimeters) compared to the male urethra (approximately 20 centimeters), making it easier for bacteria to reach the bladder and cause infection.

Q: Can pelvic anatomy change after menopause?

A: Yes, after menopause, the reproductive organs gradually atrophy due to decreased estrogen production. The vaginal tissue becomes thinner and drier, and the pelvic floor muscles may weaken over time, potentially increasing the risk of pelvic floor dysfunction.

References

- Current Concepts of Female Pelvic Anatomy and Physiology — Johns Hopkins University, Department of Urology. 1991. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2017803/

- Female Reproductive Anatomy — American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). 2024. https://www.acog.org

- Pelvic Floor Anatomy and Function — National Institutes of Health (NIH). 2023. https://www.nih.gov

Read full bio of Sneha Tete