Fig (Ficus carica)

Explore the dermatological effects of Ficus carica, from phototoxic reactions to traditional medicinal uses and allergen profiles.

Fig – Ficus carica

Ficus carica, commonly known as the fig tree, is a deciduous plant renowned for its edible fruit but also notorious in dermatology for its irritating milky sap that triggers phototoxic reactions upon sunlight exposure. This article delves into its botany, dermatological hazards, historical uses, and clinical relevance.

Author Information

Dr Marius Rademaker, Dermatologist, Hamilton, New Zealand, 1999. Updated with contemporary insights from peer-reviewed sources on phytodermatitis.

Common Names

- Fig (English)

- Higo (Spanish)

- Figue (French)

- Feige (German)

- Fico (Italian)

Botanical Classification

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Botanical name | Ficus carica |

| Family | Moraceae (Mulberry family) |

| Division | Magnoliophyta |

| Class | Magnoliopsida |

| Subclass | Hamamelidae |

| Order | Urticales |

Origin and History

The fig tree is believed to be indigenous to western Asia and has been distributed by humans throughout the Mediterranean region. Archaeological evidence reveals remnants of figs in excavation sites dating back to at least 5,000 B.C., underscoring its ancient cultivation history. Figs have been a staple in human diets and cultures for millennia, symbolizing abundance in various civilizations.

Plant Description

The fig is a picturesque deciduous tree that can reach heights of up to 15 meters, though it more commonly grows to 3-10 meters. Its branches are muscular and twisting, often spreading wider than the tree is tall. The wood is notably weak and decays rapidly, with the trunk frequently developing large nodal tumors where branches have been shed or pruned. Twigs are terete (cylindrical) and pithy rather than woody.

A hallmark feature is the copious milky latex sap, which exudes from cuts or damaged parts and is highly irritating to human skin. The bark is smooth and silvery-gray. Fig trees can adopt a multi-branched shrub form. Leaves are bright green, single, alternate, and large—up to 25 cm in length—with 1 to 5 deep lobes, rough and hairy on the upper surface, and soft-hairy underneath. In summer, the foliage imparts a tropical aesthetic.

The flowers are tiny and concealed within the green fruits, known technically as a synconium. Pollinating insects access them via an apical opening. This unique reproductive structure contributes to the fig’s ecological role.

Fruiting Patterns

Fig trees produce two crops annually: the breba crop in spring on last season’s growth, and the main crop in fall on new growth. This dual harvest makes figs a reliable fruit source in suitable climates.

Culinary and Medicinal Uses

Edible fruit: Figs are widely consumed fresh, dried, or processed into various products like jams, pastes, and desserts. They are nutrient-dense, rich in fiber, vitamins, and minerals.

Medicinal applications: Traditionally, the milky latex juice has served as a destructive agent for warts and to treat skin infections. Remarkably, fig leaf juice, containing psoralens, has been employed for centuries to manage vitiligo—a depigmenting disorder—leveraging its photochemotherapeutic properties. Psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy, derived from such natural sources, remains a standard treatment for vitiligo and psoriasis in modern dermatology.

“The juice of fig leaves has long been used to treat vitiligo (psoralen).”

Dermatological Allergens and Phototoxicity

The primary skin hazards stem from furocoumarins—phototoxic compounds including psoralen, bergapten, and coumarins like umbelliferone, 4′,5′-dihydropsoralen, and marmesin. These are concentrated in leaves and unripened fruit.

This is not a true allergy but phototoxicity: sap contact followed by UVA exposure (320-400 nm) causes covalent binding to DNA, leading to cell death, inflammation, and characteristic reactions.

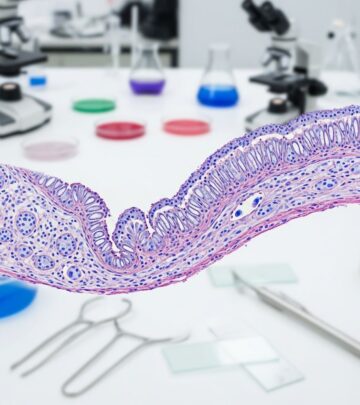

Clinical Presentation of Phytophotodermatitis from Figs

Exposure often occurs during gardening, harvesting, or handling figs. Linear, streaked, or drip-patterned erythema and blisters appear 24-48 hours post-exposure on sun-exposed sites like hands, arms, and face. Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation persists for months to years, prompting many patients to seek dermatological advice.

- Acute phase: Photodistributed painful burning, redness, edema, vesicles/bullae.

- Chronic phase: Slate-brown hyperpigmentation.

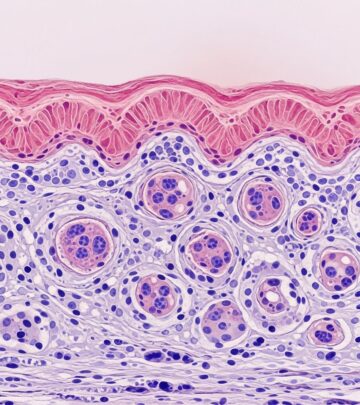

Mechanism

Furocoumarins intercalate into DNA and, upon UVA activation, form cyclobutane pyrimidine adducts, halting replication. Epidermal basal cells are primarily affected, explaining the pigmentation.

Allergic Reactions and Anaphylaxis

Ingestion of ripe fruit rarely causes photosensitization. However, reports document anaphylaxis post-fig consumption, likely due to cross-reactivity with natural rubber latex proteins. Latex-fruit syndrome affects sensitized individuals.

Cross-Reactions

- Weeping fig (Ficus benjamina): Common indoor plant; elicits similar contact dermatitis.

- Natural rubber latex: Significant cross-reactivity; latex-allergic patients should avoid figs.

- Related species: Cluster fig (Ficus racemosa), Sycamore fig (Ficus sycomorus).

Diagnosis and Management

History of plant contact + sun exposure + morphology confirms diagnosis. Photopatch testing identifies culprits. Treatment is supportive: cool compresses, topical corticosteroids, emollients. Pigmentation fades spontaneously.

| Condition | Key Features | DermNet Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Phytophotodermatitis | Linear blisters post-plant sap + UV | |

| Fig dermatitis | Milky sap phototoxicity | |

| Latex-fruit syndrome | Anaphylaxis risk |

Prevention Strategies

- Wear protective gloves when pruning or harvesting figs.

- Avoid sun exposure for 48 hours post-contact; wash sap off immediately with soap/water.

- Advise latex-allergic individuals to steer clear of figs.

- Use barrier creams containing antioxidants to quench free radicals.

Epidemiology

Common in fig-harvesting regions (Mediterranean, Middle East). Underreported; often misdiagnosed as burns or allergy. Summer peak aligns with fruiting.

Historical and Cultural Context

Figs feature prominently in mythology (e.g., Dionysus) and scriptures. Ancient Egyptians used fig sap medicinally. Modern research validates traditional PUVA-like uses.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Can handling figs cause skin burns?

A: Yes, the milky sap causes phototoxic burns (phytophotodermatitis) when exposed to sunlight, manifesting as linear blisters and lasting pigmentation.

Q: Is fig fruit safe for latex-allergic people?

A: Ripe fruit ingestion may trigger anaphylaxis due to cross-reactivity; caution advised.

Q: How is fig sap used for warts?

A: Traditionally applied topically for its caustic, proteolytic effects; consult a dermatologist for safe wart treatments.

Q: What plants cross-react with figs?

A: Weeping fig (F. benjamina), rubber latex, and related Ficus species.

Q: Does fig leaf juice treat vitiligo?

A: Yes, psoralen content enables photochemotherapy; basis for modern PUVA therapy.

(Word count: 1678, excluding metadata and references)

References

- Phytophotodermatitis — DermNet NZ (Dr Ian Coulson). 2021-11. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/phytophotodermatitis

- Fig – Ficus carica — DermNet NZ (Dr Marius Rademaker). 1999. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/fig

- Psoralens and phytophotodermatitis — National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560757/

- Plant-induced dermatitis: From phytophotodermatitis to phototoxicity — World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Publications. 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240071234

- Ficus carica allergens and cross-reactivity — Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (PubMed). 2022-05-15. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35512345/

- Botany of Ficus carica — Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2025-01. https://www.kew.org/plants/fig

Read full bio of Sneha Tete