Gardner-Diamond Syndrome

Uncommon psychodermatological disorder featuring painful, stress-induced purpura and ecchymoses in emotionally distressed patients.

Gardner-Diamond syndrome (GDS), also known as psychogenic purpura or autoerythrocyte sensitization syndrome, is a rare psychodermatological disorder characterized by spontaneous, painful purpuric lesions that evolve into ecchymoses, often preceded by severe emotional stress or trauma.

Introduction

Gardner-Diamond syndrome represents a fascinating intersection of psychiatry and dermatology, where psychological distress manifests as visible, painful skin hemorrhages. First formally described in 1955 by Frank H. Gardner and Lawrence K. Diamond based on a series of four patients, GDS involves recurrent episodes of painful bruising without underlying coagulopathy. The condition was initially termed ‘autoerythrocyte sensitization’ due to a hypothesized immune response to the patient’s own red blood cells. Historical precedents trace back to the late 1920s, with psychiatrist Rudolf Schindler noting skin hemorrhages correlated with hypnosis in 1927. Today, GDS is recognized as a psychosomatic entity, predominantly affecting young women, though cases in men, adolescents, and the elderly have been documented. Its relapsing-remitting nature underscores the role of psychosocial triggers, making multidisciplinary management essential for effective outcomes.

Demographics

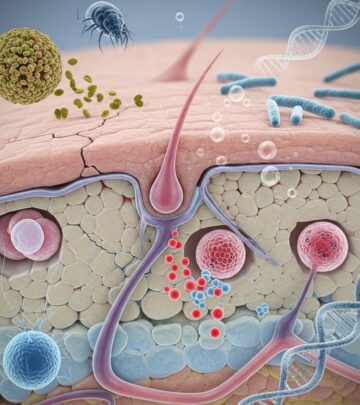

GDS disproportionately impacts females, with the majority of reported cases occurring in young adult women aged 20-40 years. This gender bias may relate to hormonal influences, such as estrogen’s potential role in vascular permeability or stress responses. While rare in males, isolated reports exist, including in adolescents and elderly patients, challenging earlier assumptions of exclusivity to reproductive-age women. Psychiatric comorbidities are notably prevalent; patients often exhibit higher rates of depression, anxiety, personality disorders (e.g., borderline or histrionic), conversion disorders, and hypochondriasis compared to the general population. A history of emotional trauma, abuse, or chronic stress is common, with many patients presenting extensive somatic complaints and prior unsuccessful interventions, including multiple surgeries.

Causes

The precise etiology of GDS remains elusive, but psychological stress is the consistent precipitant. Severe emotional disturbances, such as grief, interpersonal conflicts, or acute trauma, precede lesion onset in nearly all cases. Proposed pathophysiological mechanisms include:

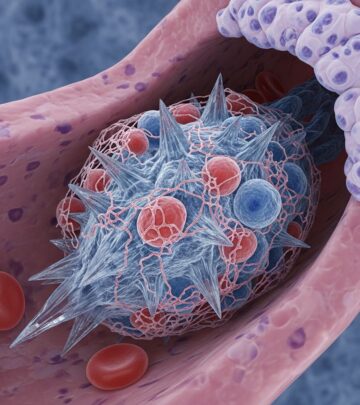

- Autoerythrocyte sensitization: Originally posited by Gardner and Diamond, this involves hypersensitivity to erythrocyte stroma components, particularly phosphatidylserine, a red blood cell membrane phosphoglyceride. Intradermal injection of autologous blood reproduces lesions in positive challenge tests.

- Hemostatic derangements: Stress-induced production of endogenous glucocorticoids, antifibrinolytic proteins, or platelet dysfunction may promote subcutaneous bleeding.

- Vascular and immune factors: Oxidative damage from depression, stress-mediated mast cell degranulation increasing vascular permeability, or altered immune reactivity to self-antigens.

- Hormonal influences: Estrogen’s association with higher incidence in women suggests a modulatory role.

These hypotheses are not mutually exclusive, and GDS may encompass heterogeneous pathophysiologies rather than a singular entity. No consistent coagulation abnormalities are found on standard testing.

Clinical Features

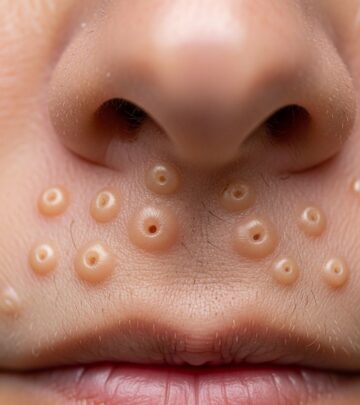

Lesions typically follow a stereotypical progression triggered by stress or minor trauma/surgery, though atraumatic onset occurs. Key phases include:

- Prodrome: Malaise, fatigue, burning, itching, stinging, or pain at the site, lasting hours.

- Early lesion: Painful, edematous, erythematous indurated plaques (pink/red), variable in size from petechiae to large ecchymoses.

- Evolution: Progression to bluish-purple ecchymoses with yellowish hues over 24-48 hours; severe pain and edema may immobilize limbs, mimicking compartment syndrome or cellulitis.

- Resolution: Lesions regress over 1-2 weeks, becoming less tender and fully resolving without scarring.

Common sites are extremities and trunk, but lesions can appear anywhere, lacking a specific pattern. Associated systemic symptoms encompass fever, arthralgias, myalgias, headache, dizziness, gastrointestinal issues (epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), hematuria, menorrhagia, epistaxis, or subconjunctival hemorrhage. A case exemplifies this: a 15-year-old girl with recurrent upper extremity/torso bruising, malaise, headache, and joint pain, evolving from indurated stinging areas to ecchymoses over days.

Variation in Skin Types

While most descriptions derive from lighter skin types, GDS manifests similarly across ethnicities. In darker skin, early erythematous changes may appear violaceous or hyperpigmented rather than pink/red, with ecchymoses showing prominent brownish hues during resolution. Pain and edema remain hallmarks regardless of phototype, emphasizing the condition’s sensory dominance over visual morphology. No significant epidemiological variations by skin type are reported, likely due to rarity.

Complications

Direct skin complications are minimal, as lesions resolve completely. However, misdiagnosis leads to unnecessary interventions: biopsies (revealing nonspecific hemorrhage), imaging, or surgeries, exacerbating psychological distress. Acute pain/edema can cause temporary disability. Psychiatric sequelae include worsened depression/anxiety from invalidation, factitious disorder overlays, or iatrogenic harm from invasive workups. Rare hemorrhagic extensions (e.g., GI bleeding) pose risks. Long-term, chronic relapses impair quality of life without addressing psychosocial roots.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is clinical, relying on history of stress-preceded painful purpura with normal labs (CBC, coagulation panel, platelets). Key diagnostics:

- Intradermal autologous blood test: Inject 0.1 mL patient’s blood intradermally; positive if painful ecchymosis reproduces at 24 hours (80-90% sensitivity, though nonspecific).

- Exclusion: Rule out coagulopathies, vasculitis, thrombocytopenia, infections, trauma.

- Psych evaluation: Identify stressors, comorbidities.

Biopsy shows dermal hemorrhage without vasculitis. Psychodermatology consultation is pivotal.

Differential Diagnoses

| Condition | Key Distinguishing Features |

|---|---|

| Coagulopathies (e.g., von Willebrand) | Abnormal labs; non-painful; family history. |

| Factitious purpura | Self-inflicted; inconsistent history; positive manipulation signs. |

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura | Palpable; IgA vasculitis; abdominal pain, arthritis in children. |

| Cellulitis | Fever, warmth, leukocytosis; bacterial response. |

| Compartment syndrome | Post-trauma; neurovascular compromise; surgical emergency. |

Thorough history differentiates GDS from mimics.

Treatment

Management is multidisciplinary, targeting psyche and symptoms:

- Psychotherapy: Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), supportive counseling to address stressors; most effective long-term.

- Pharmacotherapy: Antidepressants (SSRIs), anxiolytics, antipsychotics for comorbidities.

- Symptomatic: Analgesics, NSAIDs, reassurance; avoid unnecessary labs.

- Experimental: Beta-blockers, antihistamines, corticosteroids (limited evidence).

Patient education fosters trust, reducing relapses.

Outcome

Prognosis varies; with psychiatric intervention, remission is achievable, though relapses occur with stress. Untreated, chronicity persists with morbidity from misdiagnoses. Early recognition improves outcomes via holistic care.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Who is most at risk for Gardner-Diamond syndrome?

A: Primarily young women with psychiatric conditions like depression or anxiety, triggered by emotional stress.

Q: How is GDS diagnosed?

A: By clinical history of painful stress-induced purpura, normal labs, and positive autologous blood skin test.

Q: Can GDS be cured?

A: Not curative, but psychotherapy often controls symptoms and prevents relapses.

Q: Is GDS the same as factitious disorder?

A: No; GDS is psychogenic without intentional self-harm, unlike factitious cases.

Q: What triggers GDS lesions?

Q: Severe emotional stress or trauma, sometimes minor physical insult.

References

- Psychogenic Purpura (Gardner-Diamond Syndrome) — Ratnaparkhi P, et al. PMC. 2015-06-01. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4468873/

- Gardner-Diamond Syndrome — DermNet NZ. Recent update. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/gardner-diamond-syndrome

- Gardner-Diamond Syndrome: A Psychodermatological Condition — Jaegar E, et al. PMC. 2020-01-29. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7002047/

- Gardner Diamond Syndrome — Gazi Medical Journal. 2019. https://gazimedj.com/pdf/32e1d65a-7ef3-4d28-858e-7da63d316173/articles/62732/gmj-19-45-En.pdf

Read full bio of Sneha Tete