Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer Syndrome

Rare genetic disorder causing skin leiomyomas, uterine fibroids, and aggressive kidney cancer risk.

Author: Dermatological Society

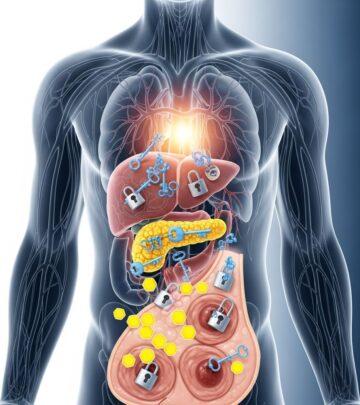

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterised by cutaneous and uterine smooth muscle tumours (leiomyomas) and an increased risk of renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

What is hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer syndrome?

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) syndrome, also known as Reed syndrome, is an inherited condition caused by heterozygous germline mutations in the FH gene on chromosome 1q43. The fumarate hydratase enzyme, encoded by FH, plays a critical role in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle by converting fumarate to malate. Pathogenic variants inactivate this enzyme, leading to fumarate accumulation, metabolic dysregulation, HIF stabilisation, and increased risk of tumorigenesis.

The syndrome manifests with multiple cutaneous piloleiomyomas (painful skin-coloured to red-brown papules or nodules), early-onset symptomatic uterine leiomyomas in females (often requiring hysterectomy), and a lifetime risk of aggressive type 2 papillary renal cell carcinoma estimated at 15–30%. Renal tumours in HLRCC are typically solitary, unilateral, and occur at younger ages (median ~40 years), with high metastatic potential even when small (<3 cm).

Who gets hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer syndrome?

HLRCC affects individuals with germline FH pathogenic variants, inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern (50% risk to each offspring). Penetrance for cutaneous leiomyomas approaches 100% by adulthood, while uterine leiomyomas affect ~80–90% of females, often by age 30. Renal cell carcinoma risk is 15–30% lifetime, with ~1–2% risk before age 20.

No clear genotype-phenotype correlations exist; renal cancer risk does not vary significantly by mutation type or family history. Both sexes are equally affected by skin and renal manifestations, but uterine involvement is female-specific.

What causes hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer syndrome?

HLRCC results from heterozygous germline mutations in FH (OMIM *136850*), with somatic second-hit mutations driving tumourigenesis. Over 200 pathogenic variants have been identified, including missense, nonsense, frameshift, and large deletions. Biallelic FH inactivation disrupts TCA cycle function, causing oncometabolite accumulation (fumarate), pseudohypoxia (HIFα stabilisation), DNA hypermethylation, and protein succination, promoting oncogenesis.

What are the clinical features of hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer syndrome?

Cutaneous leiomyomas

Skin leiomyomas (piloleiomyomas) are the most common initial manifestation, appearing in 75–95% of patients as multiple firm, reddish-brown papules or nodules (2–20 mm) on the trunk, limbs, face, or buttocks. They often occur in segmental patterns and cause intense pain triggered by cold, pressure, or emotion due to smooth muscle contraction. Lesions increase in number and size over time.

Uterine leiomyomas

Females develop numerous, early-onset (teens–30s) uterine fibroids causing pain, heavy bleeding, and infertility, frequently necessitating myomectomy or hysterectomy. Risk of uterine leiomyosarcoma is elevated but remains rare (~1%).

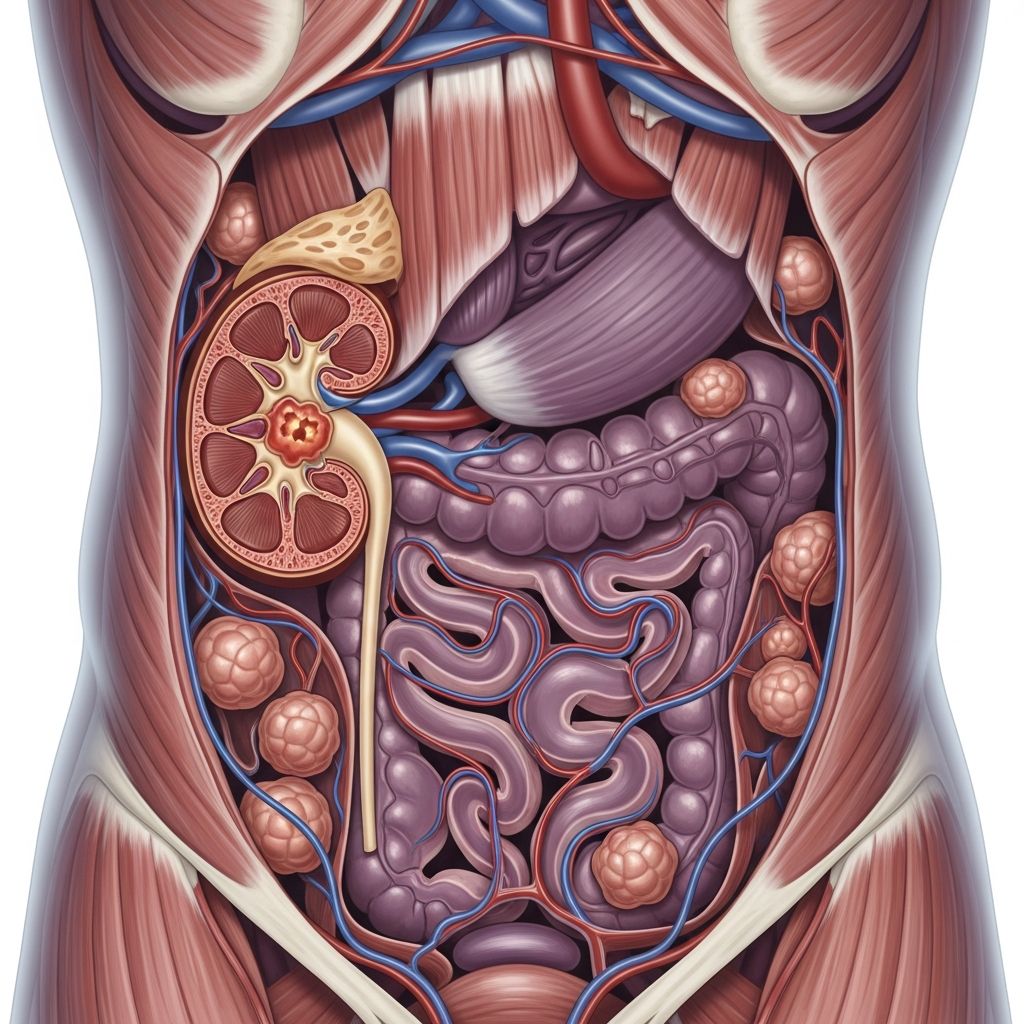

Renal cell carcinoma

HLRCC-associated RCC is predominantly type 2 papillary (80–90%), with characteristic large nucleoli and perinucleolar halos histologically. Tumours are solitary (90%), unilateral, and aggressive, metastasising early despite small size. Median age at diagnosis is 35–44 years.

Other manifestations

- Adnexal cysts (ovarian/testicular)

- Prostate cancer (rare case reports)

- Colon/colorectal cancer (suggested association)

- Breast cancer (limited evidence)

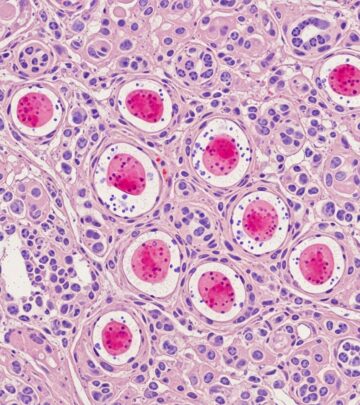

Pathology of HLRCC-associated tumours

Cutaneous and uterine leiomyomas

Histology shows intersecting smooth muscle fascicles in the dermis/subcutis with entrapped collagen; immunoreactivity for smooth muscle actin, desmin, and ERα.

Renal cell carcinoma

Type 2 papillary RCC with prominent nucleoli (Fuhrman grade 3/4), tumour giant cells, and rhabdoid features. IHC shows FH loss (88%), 2SC positivity (succination marker), and FH gene sequencing confirms biallelic inactivation.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis combines clinical features, family history, and genetic testing:

- Clinical criteria: ≥2 cutaneous leiomyomas or 1 cutaneous leiomyoma + family history of HLRCC features.

- Genetic testing: FH sequencing/deletion analysis (yield ~90% in suspicious cases).

- Tumour testing: FH IHC (negative) or 2SC positivity in RCC/leiomyomas.

Amsterdam criteria or NCCN guidelines aid RCC predisposition syndrome evaluation.

Screening and surveillance for HLRCC

| Manifestation | Screening Recommendation | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Renal cell carcinoma | MRI or CT abdomen/pelvis | Annually from age 8–10 years |

| Cutaneous leiomyomas | Skin examination | Annually from diagnosis |

| Uterine leiomyomas | TVUS or MRI pelvis | Annually from age 20 in females |

At-risk relatives: predictive FH testing from age 8–10 if parent affected. Partial nephrectomy preferred for localised RCC; metastasectomy/tyrosine kinase inhibitors for advanced disease.

Management

- Skin leiomyomas: Observation, topical aspirin/nifedipine, cryotherapy, CO2 laser, or excision for painful lesions.

- Uterine leiomyomas: NSAIDs, hormonal therapy, myomectomy, hysterectomy.

- RCC: Nephron-sparing surgery; VEGF/mTOR inhibitors (sunitinib, everolimus).

Investigations to consider

- FH germline sequencing

- Renal MRI/CT

- Dermatological exam/biopsy

- Gynaecological ultrasound

- Family history pedigree

Differential diagnosis

| Condition | Distinguishing Features |

|---|---|

| Multiple piloleiomyomas (non-HLRCC) | No FH mutation, no RCC risk |

| Familial RCC syndromes (VHL, HPRC) | Different histology, other tumours |

| Sporadic uterine fibroids | Later onset, solitary |

Disease severity and prognosis

Prognosis depends on RCC development and early detection. Skin/uterine leiomyomas cause morbidity but are benign. RCC is aggressive (5-year survival ~20–60% if metastatic). Lifelong surveillance improves outcomes.

Frequently asked questions

What is the lifetime renal cancer risk in HLRCC?

The estimated lifetime risk for FH mutation carriers is 15–30%, with early onset possible.

At what age should screening begin?

Renal imaging recommended annually from ages 8–10 years in known/presumed carriers.

Are cutaneous leiomyomas painful?

Yes, often triggered by cold, touch, or stress due to smooth muscle contraction.

Can HLRCC be prevented?

No, but early screening and surgical intervention improve prognosis.

Is genetic testing recommended for family members?

Yes, predictive testing from childhood for at-risk relatives.

References

- Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC). Renal manifestations — PMC/NCBI. 2015. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4574691/

- Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer — HLRCC Family Alliance. 2023. https://hlrcc.org

- Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer syndrome — NCI PDQ. 2024-01-15. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/pdq/information-summaries/genetics/hlrcc-syndrome-hp-pdq

- FH Tumor Predisposition Syndrome — GeneReviews/NCBI. 2023-09-28. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1252/

- Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Carcinoma — NORD. 2022. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/hereditary-leiomyomatosis-and-renal-cell-carcinoma/

Read full bio of Sneha Tete