Legius Syndrome

Rare genetic disorder mimicking NF1 with café-au-lait macules but no tumours: causes, diagnosis, and management.

Legius syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant genetic disorder characterised by multiple café-au-lait macules and skinfold freckling, resembling neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) but without neurofibromas or other tumour risks. First described in 2007, it belongs to the group of RASopathies, conditions caused by mutations affecting the RAS-MAPK signalling pathway, leading to altered cell communication and pigmentation changes. Unlike NF1, Legius syndrome has a milder phenotype focused on cutaneous and neurodevelopmental features, making accurate genetic diagnosis essential for appropriate management.

Introduction

Legius syndrome, also known as NF1-like syndrome, presents primarily with pigmentary skin lesions that mimic the early features of NF1, often leading to diagnostic confusion. Named after Eric Legius who identified its genetic basis, the condition affects cell signalling via the RAS pathway, resulting in hyperpigmented macules without the oncogenic risks associated with NF1. Patients typically exhibit multiple light-brown café-au-lait macules (CALMs), axillary or inguinal freckling, and sometimes mild cognitive or developmental delays. The absence of tumours distinguishes it clinically over time, but genetic testing is required for confirmation, especially in young children where NF1 features may not yet be evident. This syndrome underscores the importance of molecular diagnostics in paediatric dermatology and genetics, as it influences surveillance strategies and family counselling. Prevalence is estimated to be lower than NF1 (1 in 3,000), with Legius syndrome occurring in approximately 1 in 70,000 to 100,000 individuals, though underdiagnosis is likely due to its benign nature.

Demographics

Legius syndrome affects individuals of all ethnic backgrounds, with no strong sex predilection reported, consistent with its autosomal dominant inheritance. It is typically diagnosed in childhood, often by age 1-5 years when CALMs become prominent. Familial cases predominate, but sporadic de novo mutations occur in about 50% of patients, mirroring NF1 patterns. Higher recognition has occurred in populations with access to genetic testing, such as in Europe and North America where research centres like KU Leuven have contributed significantly. Children from families with NF1 history are frequently tested to rule out Legius syndrome if tumours are absent. Global registries, such as those from the National Organization for Rare Disorders, highlight its rarity, with fewer than 300 cases reported worldwide as of recent data.

Causes

The primary cause of Legius syndrome is heterozygous germline mutations in the SPRED1 gene located on chromosome 12q13.13-q14.1. The SPRED1 protein negatively regulates the RAS-MAPK/ERK pathway, which is critical for cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival. Pathogenic variants, including nonsense, frameshift, splice site, and missense mutations, lead to loss of function, resulting in pathway hyperactivation akin to NF1 but without tumour predisposition. Over 100 unique SPRED1 mutations have been identified, with no clear genotype-phenotype correlations established due to variable expressivity. Inheritance is autosomal dominant with high penetrance for CALMs (nearly 100%), though expressivity varies. De novo mutations account for half of cases, emphasising the need for parental testing. As a RASopathy, it shares molecular mechanisms with Noonan syndrome and Costello syndrome, but cutaneous features are most NF1-like.

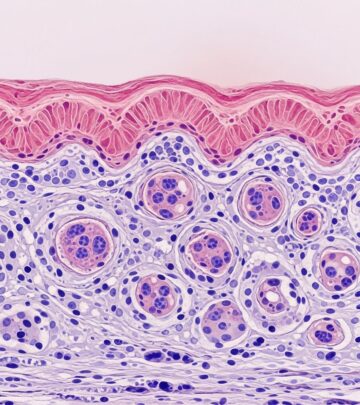

Clinical Features

The hallmark of Legius syndrome is multiple café-au-lait macules, present in nearly all patients, appearing as light- to medium-brown, oval or irregular patches greater than 5 mm in children or 15 mm in adults. These increase in number and size during early childhood, often numbering 6 or more. Skinfold freckling in axillary or inguinal regions emerges by age 6, appearing as small hyperpigmented papules.

Other common cutaneous features include:

- Occasional lipomas in adulthood

- Mild skin hyperpigmentation without neurofibromas

- No iris Lisch nodules or optic gliomas

Non-cutaneous features are milder than in NF1 and may include:

- Macrocephaly (large head circumference)

- Mild developmental delay, learning difficulties, or ADHD-like behaviours

- Short stature

- Hypertelorism (wide-set eyes) or mild facial dysmorphism like pectus excavatum

Clinical variability is significant; some individuals are asymptomatic beyond CALMs, while others exhibit neurocognitive challenges requiring support. No increased malignancy risk is established, though long-term studies are limited.

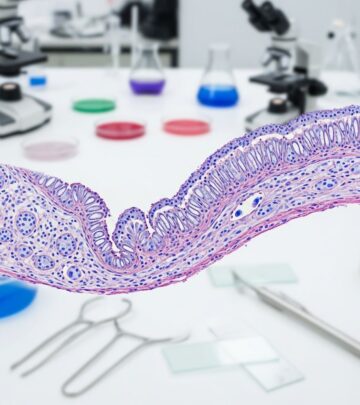

Diagnosis

Diagnosis relies on genetic confirmation due to clinical overlap with NF1. Suspicious findings prompting testing include multiple CALMs (≥6) with or without freckling in the absence of NF1 criteria like neurofibromas or Lisch nodules. Testing involves:

- Sequencing and deletion/duplication analysis of SPRED1

- Targeted NF1/SPRED1 panels if NF1 is also suspected

- Confirmation of pathogenicity per ACMG guidelines

Clinical scoring is not formalised, but NIH NF1 criteria minus tumours suggest Legius. Prenatal or preimplantation testing is available for at-risk families.

Differential Diagnoses

Legius syndrome must be differentiated from other conditions with multiple CALMs:

| Condition | Key Features | Distinguishing from Legius |

|---|---|---|

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) | CALMs, freckling, neurofibromas, Lisch nodules, tumours | Presence of tumours, optic gliomas; NF1 gene mutation |

| Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD) | CALMs, NF1-like features, family cancer history | Cancer risk (brain, GI); biallelic MMR gene mutations |

| Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines | Lentigines, cardiac defects, short stature | Ptosis, hypertelorism, PTPN11 mutations |

| McCune-Albright syndrome | Irregular “coast of Maine” CALMs, fibrous dysplasia | Endocrine issues, GNAS mosaicism |

| Piebaldism | Depigmented patches, white forelock | Hypopigmentation dominant, KIT mutations |

Genetic testing resolves most differentials.

Treatment

Treatment is supportive, targeting symptoms:

- Skin: Cosmetic laser therapy for CALMs if distressing; monitor lipomas

- Neurodevelopmental: Educational support, speech/occupational therapy, behavioural interventions for ADHD

- Multidisciplinary care: Paediatrics, dermatology, genetics, neurology; annual screening for delays

- No tumour surveillance needed, unlike NF1

Genetic counselling for 50% recurrence risk is crucial.

Outcome

Prognosis is excellent with normal lifespan and no malignancy risk. Intellectual disability is rare; most achieve independence with support for mild learning issues. Regular monitoring optimises outcomes, and family planning considers inheritance. Ongoing research may refine management.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Is Legius syndrome the same as NF1?

A: No, Legius syndrome mimics NF1 skin features but lacks tumours and is caused by SPRED1 mutations.

Q: Can Legius syndrome cause cancer?

A: No increased risk is documented, unlike NF1.

Q: How is Legius syndrome inherited?

A: Autosomal dominant; 50% chance per child.

Q: Do all patients have learning problems?

A: No, mild delays occur in some; many are unaffected cognitively.

Q: When should genetic testing be done?

A: In children with ≥6 CALMs without NF1 features.

References

- Legius syndrome – DermNet — DermNet NZ. 2023. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/legius-syndrome

- Legius Syndrome — Rady Children’s Hospital. 2024-01-15. https://www.rchsd.org/health-article/legius-syndrome/

- Legius Syndrome and its Relationship with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 — Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 2023-05-10. https://www.medicaljournals.se/acta/content/html/10.2340/00015555-3429

- Legius Syndrome (for Parents) — KidsHealth. 2024. https://kidshealth.org/HumanaKentucky/en/parents/legius-syndrome.html

- Legius syndrome — NORD / MONDO. 2025-01-01. https://rarediseases.org/mondo-disease/legius-syndrome/

- Legius Syndrome – GeneReviews® — NCBI Bookshelf (University of Washington). 2024-06-20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47312/

Read full bio of Sneha Tete