Mycobacterium marinum Skin Infection Pathology

Detailed histopathological analysis of Mycobacterium marinum skin infections, from granulomatous dermatitis to diagnostic challenges.

Mycobacterium marinum is a non-tuberculous mycobacterium that causes skin infections primarily associated with exposure to contaminated water, such as aquariums or swimming pools, leading to the characteristic “fish tank granuloma” or “swimming pool granuloma.” The histopathological features of these infections are diverse, reflecting the lesion’s age and host response, and are crucial for diagnosis when clinical suspicion alone is insufficient.

Histopathology images

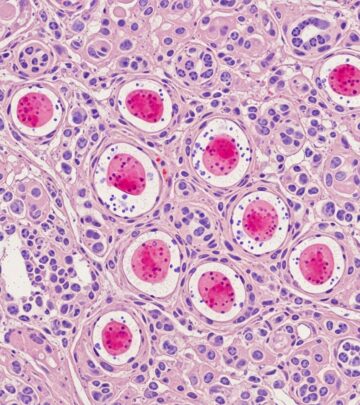

Key microscopic views illustrate the spectrum of pathological changes in Mycobacterium marinum infections:

- Scanning power view: Reveals granulomatous dermatitis with nodular dermal infiltrates (Figure 1).

- Tuberculoid granulomas: Show abscess formation and mixed inflammation (Figure 2).

- High-power details: Lymphohistiocytic infiltrates with multinucleated giant cells and neutrophils (Figures 3, 4).

- Ulcerated lesions: Demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and suppurative granulomas (Figures 2A-E from clinical series).

- Deep tissue: Necrotizing granulomas in synovium with fibrin exudation (Figures 2F-H).

These images highlight the progression from early suppurative responses to mature granuloma formation.

Introduction

Mycobacterium marinum thrives in aquatic environments at temperatures of 28-32°C, infecting humans via skin abrasions from fish tanks, natural waters, or fish handling. Infections manifest as painless purple nodules on extremities, progressing to ulcers or sporotrichoid patterns along lymphatics. Histopathology is pivotal, showing granulomatous inflammation, though acid-fast bacilli (AFB) are often sparse, necessitating culture or PCR for confirmation. This article details the microscopic evolution, aiding pathologists in recognizing this entity amid mimics like fungal infections or other mycobacteria.

Early lesions

Early Mycobacterium marinum lesions exhibit an acute suppurative inflammatory process with minimal granuloma formation. Microscopically, there is a brisk neutrophilic infiltrate forming microabscesses in the superficial dermis, accompanied by dermal edema and early lymphocytic response. Epidermal changes include spongiosis or subtle hyperplasia, without ulceration at this stage.

In a series of 63 proven cases, 20% showed neutrophil collections without granulomas, underscoring this pattern’s frequency in nascent infections. Superficial dermal abscesses with lymphocytic infiltration, as seen in a recent hand infection case, confirm acute inflammation as an initial hallmark (H&E, 100x). This phase mimics bacterial cellulitis but progresses to granulomatous organization within weeks.

Well-developed lesions

Scanning power views of mature lesions demonstrate a

granulomatous dermatitis

with extensive nodular infiltrates filling the dermis (Figure 1). The infiltrate comprises epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells (Langhans-type), and lymphocytes, forming tuberculoid granulomas with variable central necrosis or suppuration (Figure 2).Poorly formed granulomas—loose aggregates of epithelioid macrophages and scattered giants—predominate (96% of biopsies), while well-formed nodular granulomas occur less often (54%). Peripheral granulation tissue and mixed inflammation rim these structures. In deep soft tissue or synovial samples, necrotizing suppurative granulomas with synoviocyte hyperplasia are consistent findings. The mixed lymphohistiocytic background with neutrophils reflects ongoing suppuration.

Epidermal changes

The epidermis often displays

pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia

(PEH), a reactive psoriasiform or acanthotic proliferation mimicking squamous cell carcinoma, especially at ulcer edges. Ulceration, present in up to 37% of cases, shows granulation tissue and scale crust.Hyperkeratosis and hyperplasia of squamous epithelium are noted, with dermo-epidermal junction invasion in select cases. Follicular necrosis occurs in 6% (4/63 cases), adding diagnostic nuance. These changes, while non-specific, correlate with chronicity and surface breakdown.

Late lesions

Chronic lesions evolve into fibrotic scars with residual granulomas amid dense collagen. Persistent inflammation may involve deeper structures like tenosynovium (28% of cases), showing synovial fibrin exudation and giant cell reaction. In immunocompromised hosts, dissemination risks rise, though prognosis remains good with treatment.

Non-specific infiltrates (lymphoplasmacytic, remote from granulomas) appear in 20% of biopsies, complicating diagnosis without microbiology. Tenosynovitis or osteomyelitis signals advanced disease, histologically mirroring skin granulomas but with bone erosion.

Special stains

Acid-fast stains (Ziehl-Neelsen or Fite) reveal rare, slender bacilli within granuloma cores, often requiring multiple levels due to low burden. IHC for mycobacteria enhances detection, staining bacilli and antigens more extensively than AFB. PAS or silver stains rule out fungi, which show yeast forms absent here.

| Feature | M. marinum | TB | Fungi |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFB/IHC | Rare bacilli in necrosis | Paucibacillary | Negative |

| Granuloma | Suppurative, loose | Caseating, well-formed | Suppurative w/ organisms |

| PAS/GMS | Negative | Negative | Positive (yeasts) |

Cultures at 30°C and PCR are gold standards for speciation.

Cytology

Fine-needle aspiration yields granulomatous material with giant cells and possible AFB, useful for inaccessible lesions. Cytologic smears show suppurative granulomas mirroring histology, aiding rapid triage.

Electron microscopy

Ultrastructurally, bacilli appear as rod-shaped organisms with trilaminar cell walls within histiocytes, confirming mycobacterial identity when light microscopy fails. Rarely used clinically due to advanced molecular diagnostics.

Differential diagnosis

Histology alone cannot speciate; consider:

- Other NTM: More neutrophils, interstitial granulomas, vessel proliferation.

- TB/Leprosy: Caseation, fewer bacilli.

- Fungi: Suppurative granulomas with PAS/GMS-positive elements.

- Sporotrichosis/Nocardia: Asteroid bodies or filaments.

- Pyoderma gangrenosum: Less organized inflammation.

Deep fungal infections mimic closely but yield organisms on special stains. Culture/PCR resolves ambiguities.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the hallmark histopathology of M. marinum infection?

Granulomatous dermatitis with suppurative tuberculoid granulomas, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and rare AFB.

Why are bacilli hard to find?

The low bacterial load distinguishes it from other mycobacteria; IHC improves yield.

Can it affect deep tissues?

Yes, tenosynovitis in 28% shows necrotizing granulomas in synovium.

How to differentiate from fungal infection?

Negative PAS/GMS; PCR/culture confirms.

Prognosis with pathology?

Excellent in immunocompetent; deeper involvement predicts slower resolution.

References

- Mycobacterium marinum skin infection pathology — DermNet NZ. 2023. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/mycobacterium-marinum-skin-infection-pathology

- Clinical and Pathological Evaluation of Mycobacterium marinum Infections — Clinical Infectious Diseases (Oxford Academic). 2016-02-15. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article-abstract/62/5/590/2462766

- [Histopathological study of Mycobacterium marinum infection] — PubMed (French study). 2011. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21276456/

- Mycobacterium marinum hand infection: a case report and literature review — Frontiers in Medicine. 2024. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2024.1433153/full

- Mycobacterium marinum Infection — StatPearls, NCBI Bookshelf (NIH). 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441883/

Read full bio of medha deb