Portal Hypertension Treatment Options

Comprehensive guide to managing portal hypertension through medical and surgical interventions.

Understanding Portal Hypertension Treatment

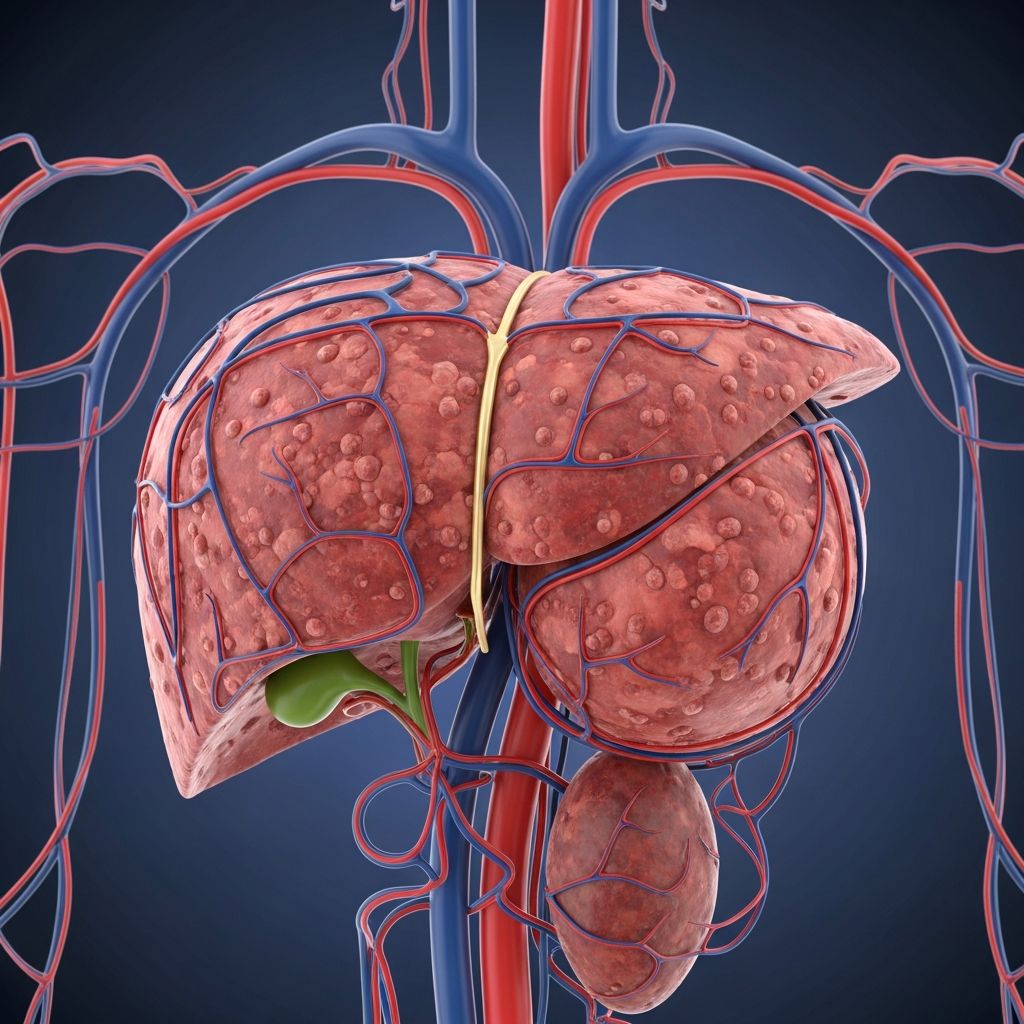

Portal hypertension occurs when blood pressure in the portal vein—the vessel that carries blood from the digestive organs to the liver—becomes abnormally elevated. This condition typically develops as a result of liver cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis, or other liver diseases that obstruct normal blood flow. The elevated pressure can lead to serious complications including the formation of enlarged veins (varices) in the esophagus and stomach, which carry a significant risk of life-threatening bleeding.

Treatment for portal hypertension aims to reduce portal pressure, prevent bleeding from varices, and manage the complications associated with the condition. A comprehensive approach often involves a combination of medical therapies, endoscopic interventions, and in some cases, surgical procedures. The specific treatment plan depends on the severity of portal hypertension, the underlying cause, and the presence of complications such as active bleeding or ascites (fluid accumulation in the abdomen).

Medical Management of Portal Hypertension

Beta-Blockers and Pharmacological Therapy

Pharmacological management forms the cornerstone of portal hypertension treatment, particularly for primary prevention of variceal bleeding. Beta-blockers are the most commonly prescribed medications for this purpose. These drugs work by reducing portal pressure and decreasing the risk of variceal rupture. The most frequently used beta-blockers include propranolol, nadolol, and carvedilol.

Propranolol reduces portal pressure by decreasing cardiac output and causing splanchnic vasoconstriction. Nadolol offers similar benefits with the advantage of once-daily dosing, improving patient compliance. Carvedilol, a newer agent, combines non-selective beta-blocking properties with alpha-blocking activity, providing superior hemodynamic effects in some patient populations. The choice of beta-blocker depends on individual patient tolerance and response to therapy.

Beta-blockers are typically continued indefinitely in patients with portal hypertension, even if they have not yet experienced variceal bleeding. Studies demonstrate that long-term beta-blocker therapy significantly reduces the incidence of first variceal bleeding events and improves overall survival rates. Dosing is titrated based on heart rate response and blood pressure monitoring to ensure therapeutic efficacy while maintaining acceptable tolerability.

Nitrates and Combination Therapy

Long-acting nitrates such as isosorbide mononitrate are sometimes used in combination with beta-blockers to enhance portal pressure reduction. Nitrates work through vasodilation mechanisms, reducing both portal and systemic vascular resistance. When combined with beta-blockers, they may provide additive benefits in preventing variceal bleeding, though individual patient responses vary considerably.

The combination of beta-blockers and nitrates appears particularly beneficial in patients who have already experienced variceal bleeding, as part of secondary prophylaxis strategies. However, nitrate tolerance can develop with continuous exposure, requiring dose adjustment or intermittent dosing schedules to maintain efficacy.

Endoscopic Management

Endoscopic Variceal Ligation

Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) has become the preferred endoscopic procedure for managing esophageal varices. During this minimally invasive procedure, a physician uses an endoscope to visualize the enlarged varices and applies elastic bands around them, effectively cutting off their blood supply. The varices subsequently slough off, allowing the underlying tissue to heal.

EVL offers several advantages over older techniques. It can be performed safely in outpatient settings with minimal sedation, has lower complication rates than alternatives, and demonstrates superior efficacy in preventing rebleeding. Most patients require multiple sessions spaced one to two weeks apart until all varices are obliterated. Once variceal eradication is confirmed through follow-up endoscopy, surveillance endoscopies are performed at regular intervals to detect recurrence early.

EVL is typically recommended for patients with medium to large varices, those with signs of recent bleeding (red wale marks or clots), and those with high-risk features. It serves as both primary prophylaxis in suitable candidates and secondary prophylaxis following an initial bleeding episode.

Endoscopic Sclerotherapy

Endoscopic sclerotherapy involves injection of sclerosing agents directly into or adjacent to esophageal varices through the endoscope. Common sclerosing agents include sodium tetradecyl sulfate, ethanol, and cyanoacrylate. These substances cause inflammation and thrombosis of the varices, sealing them off from the circulating blood.

While historically important, endoscopic sclerotherapy has been largely superseded by variceal ligation in many centers due to superior efficacy and lower complication rates with EVL. However, sclerotherapy remains useful for gastric varices and in settings where ligation is technically difficult. Sclerotherapy carries a higher risk of post-procedure complications, including ulceration, stricture formation, and perforation compared to ligation techniques.

Radiological Interventions

Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS)

The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) represents an important radiological intervention for managing complications of portal hypertension when medical and endoscopic therapies prove inadequate. During TIPS placement, an interventional radiologist creates a channel through the liver tissue that connects the portal vein to the hepatic vein, effectively bypassing the cirrhotic liver and reducing portal pressure.

TIPS is particularly valuable in managing acute variceal bleeding that is refractory to medical therapy and endoscopic procedures. It can also be used for secondary prophylaxis in patients who have failed other treatment modalities. Additionally, TIPS addresses other portal hypertension-related complications including refractory ascites and hepatic encephalopathy, though the latter complication can actually be worsened by TIPS in some patients.

The procedure involves minimal incisions and is performed under radiological guidance with local anesthesia and sedation. A stent is placed within the created channel to maintain patency. Follow-up ultrasound surveillance is essential to monitor stent function and detect dysfunction early, as stent thrombosis can occur in approximately 10-15% of patients within the first year, though modern covered stents have improved long-term patency rates.

Active Variceal Bleeding Management

Emergency Interventions

Variceal bleeding represents a medical emergency requiring immediate intervention. Initial management focuses on hemodynamic stabilization through fluid resuscitation, correction of coagulopathy, and platelet transfusion if necessary. Patients with variceal bleeding often have underlying coagulation abnormalities due to liver dysfunction, making appropriate laboratory monitoring and correction essential.

Pharmacological therapy with vasoactive agents should begin immediately upon suspicion of variceal bleeding, even before endoscopic confirmation. Octreotide, a somatostatin analog, is administered as a bolus followed by continuous infusion to reduce splanchnic blood flow and portal pressure. Terlipressin, a vasopressin analog with more selective splanchnic activity, offers superior hemodynamic effects in some patient populations but carries greater systemic vascular side effects.

Endoscopic therapy should be performed urgently once the patient has been stabilized. EVL is preferred over sclerotherapy for esophageal variceal bleeding due to superior outcomes. Most actively bleeding varices are successfully managed through combination of pharmacological support and endoscopic intervention, achieving hemostasis in 80-90% of cases with appropriate management.

Rescue Therapies

For bleeding that continues despite combined pharmacological and endoscopic therapy, rescue interventions become necessary. TIPS placement has revolutionized the management of refractory variceal bleeding, offering a bridge to liver transplantation in decompensated patients or providing definitive pressure reduction in those not transplant candidates. Balloon tamponade with esophageal balloon tubes represents a temporizing measure for uncontrolled bleeding but carries significant complications and should only be used as a temporary bridge to definitive therapy.

Secondary Prophylaxis

Following an initial variceal bleeding episode, secondary prophylaxis aims to prevent recurrent bleeding and improve survival. This involves continuation or initiation of beta-blocker therapy combined with repeated endoscopic variceal ligation sessions until complete variceal eradication is achieved.

Studies demonstrate that combination medical and endoscopic therapy significantly reduces rebleeding rates from approximately 60% to less than 20% in the first year. Patients typically require endoscopic surveillance at regular intervals following initial variceal eradication, with repeat procedures performed if varices recur. Long-term beta-blocker therapy is maintained indefinitely unless specific contraindications develop.

Treatment of Gastric Varices

Gastric varices present unique management challenges as they are often larger than esophageal varices, more difficult to access endoscopically, and carry higher rebleeding rates. Cyanoacrylate injection (tissue adhesive) has become the preferred endoscopic approach for gastric varices, though special expertise is required for safe application. TIPS may be considered earlier in the management of gastric variceal bleeding compared to esophageal varices due to the less satisfactory results with endoscopic therapy alone.

Portal vein thrombosis associated with gastric varices requires careful evaluation, as anticoagulation strategies may need modification in patients with actively bleeding varices versus those receiving prophylactic treatment.

Monitoring and Follow-up Care

Successful management of portal hypertension requires ongoing monitoring and adjustment of therapy based on patient response. Patients on beta-blockers require periodic assessment of heart rate and blood pressure to ensure adequate dosing and tolerance. Some experts advocate for hemodynamic monitoring during beta-blocker titration, though this is not universally practiced.

Surveillance endoscopy following variceal eradication typically occurs at 1-3 month intervals until no varices are visualized, then yearly or as clinically indicated if varices recur. Patients with portal hypertension require evaluation for hepatic encephalopathy, renal dysfunction, and other complications of advanced liver disease, which may necessitate additional interventions beyond variceal management.

Regular assessment of liver synthetic function, degree of portal hypertension, and child-Pugh or Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores helps guide the intensity of monitoring and timing of interventions. Patients meeting criteria for liver transplantation should be referred appropriately, as transplantation offers definitive treatment for end-stage liver disease with associated portal hypertension.

Complications and Special Considerations

Portal Vein Thrombosis

Portal vein thrombosis can occur in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension, complicating both diagnosis and treatment. While this condition increases variceal bleeding risk, the presence of thrombosis does not necessarily preclude TIPS placement or other interventions, though technical modifications may be necessary. Anticoagulation therapy is considered in select patients, particularly those with acute thrombosis or those requiring TIPS.

Ascites Management

While ascites may accompany portal hypertension with varices, it is addressed through separate management strategies including salt restriction, diuretics, and therapeutic paracentesis when necessary. Some medications used for variceal prevention, such as beta-blockers and nitrates, may paradoxically worsen ascites in some patients through hemodynamic effects.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How long does beta-blocker therapy need to be continued?

A: Beta-blockers for portal hypertension are typically continued indefinitely, even after variceal eradication, unless specific contraindications develop. Discontinuation is associated with increased rebleeding rates.

Q: Can portal hypertension be cured without liver transplantation?

A: While specific complications of portal hypertension (such as varices) can be effectively managed and prevented, the underlying portal hypertension typically persists unless the underlying liver disease is treated or transplantation is performed. Liver transplantation is the only definitive cure.

Q: What is the mortality rate from variceal bleeding?

A: With modern treatment approaches combining pharmacological, endoscopic, and radiological interventions, mortality from acute variceal bleeding has decreased to approximately 10-20%. However, outcomes depend significantly on the degree of liver dysfunction and overall patient condition.

Q: How often should patients with portal hypertension undergo endoscopic screening?

A: Initial endoscopic screening should be performed at diagnosis to evaluate for varices. If varices are present, frequent endoscopic treatment is needed until eradication. Following eradication, surveillance typically occurs annually or as clinically indicated if varices recur.

Q: Is TIPS placement a permanent solution?

A: TIPS effectively reduces portal pressure and prevents variceal bleeding, but stent dysfunction can occur over time. While modern covered stents have improved durability, some patients may require stent revision or replacement. TIPS is typically viewed as a bridge to transplantation or a long-term management strategy rather than a permanent cure.

References

- Pathophysiology and Management of Variceal Bleeding — Johns Hopkins University. Published April 2021 in Drugs, Volume 81, Issue 6. https://pure.johnshopkins.edu/en/publications/pathophysiology-and-management-of-variceal-bleeding

- Portal Hypertension: Pathophysiology and Clinical Manifestations — American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD Clinical Practice Guidelines. https://www.aasld.org

- Variceal Bleeding Management in Cirrhosis — European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on portal hypertension. 2023. https://www.easl.eu

- Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt: Indications and Outcomes — Society of Interventional Radiology. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. https://www.sirweb.org

- Beta-Blocker Therapy in Portal Hypertension — PubMed Central – National Center for Biotechnology Information. National Institutes of Health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc

Read full bio of Sneha Tete