Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatment

Understanding symptoms, causes, diagnosis, and treatments for primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), a chronic autoimmune liver disease.

Primary Biliary Cholangitis

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), previously known as primary biliary cirrhosis, is a

chronic autoimmune liver disease

that progressively destroys small intrahepatic bile ducts, leading to cholestasis, inflammation, fibrosis, and eventually cirrhosis in many cases.What Is Primary Biliary Cholangitis?

**Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)** is an autoimmune disorder where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the small bile ducts within the liver. These ducts, known as interlobular bile ducts, are essential for transporting bile—a digestive fluid produced by the liver—from the liver cells to the gallbladder and intestine. Over time, this immune-mediated destruction causes bile buildup (cholestasis), damaging liver cells and leading to scarring (fibrosis) and cirrhosis.

The disease primarily affects women, with a female-to-male ratio of about 9:1, and typically develops between ages 40 and 60. PBC is considered a rare disease but has significant morbidity, often requiring long-term management to slow progression and alleviate symptoms.

Symptoms of Primary Biliary Cholangitis

PBC symptoms vary widely; up to 60% of patients are asymptomatic at diagnosis, discovered incidentally through abnormal liver tests. When symptoms appear, they result from cholestasis and include:

- Fatigue: The most common symptom, affecting over 80% of patients, often profound and debilitating, impacting quality of life.

- Pruritus (itching): Occurs in 20-70% of cases due to bile salt accumulation in the skin. It worsens at night, in warm weather, or with dry skin. Recent research links it to elevated lysophosphatidic acid from autotaxin activity.

- Jaundice: Yellowing of skin and eyes from bilirubin buildup, signaling advanced disease.

- Abdominal pain: Vague right upper quadrant discomfort.

- Malabsorption and steatorrhea: Due to fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies (A, D, E, K), causing diarrhea, weight loss, and osteoporosis risk.

As PBC advances to cirrhosis, complications like portal hypertension, variceal bleeding, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy may emerge.

Causes and Risk Factors

The exact cause of PBC remains unknown, but it arises from a combination of

genetic predisposition

andenvironmental triggers

in susceptible individuals.Genetic factors: PBC prevalence is 100 times higher in first-degree relatives, indicating strong heritability. Specific genes linked to immune regulation, such as those in the HLA complex, increase risk.

Environmental triggers: Potential culprits include bacterial infections (e.g., Escherichia coli, Novosphingobium aromaticivorans), cigarette smoking, urinary tract infections, hormone replacement therapy, nail polish exposure, and xenobiotics (toxic chemicals). These mimic mitochondrial proteins, sparking an autoimmune response targeting the pyruvate dehydrogenase E2 (PDC-E2) subunit, producing anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA).

The autoimmune attack involves B cells (producing AMA) and T cells destroying bile duct epithelial cells, leading to ductopenia (bile duct loss), cholestasis, and progressive liver damage.

Pathophysiology and Histopathology

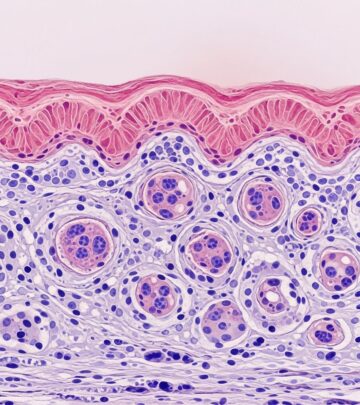

PBC pathogenesis begins with immune tolerance loss to PDC-E2 on bile duct cells. AMA binds mitochondria, while CD4+ and CD8+ T cells infiltrate portal tracts, causing nonsuppurative destructive cholangitis (florid duct lesion)—a hallmark with lymphocytic inflammation around damaged ducts.

Progression stages:

- Stage I: Portal inflammation without fibrosis.

- Stage II: Periportal inflammation and duct proliferation.

- Stage III: Fibrosis and bridging.

- Stage IV: Cirrhosis with nodule formation.

Cholestasis elevates alkaline phosphatase (ALP); prolonged damage causes hepatocyte death, fibrosis, and portal hypertension.

Diagnosis of Primary Biliary Cholangitis

Diagnosis relies on two of three criteria:

- ALP elevation ≥1.5 times upper normal limit for ≥6 months.

- Positive AMA (titer ≥1:40), present in 90-95% of cases—highly specific (98%).

- Liver biopsy showing bile duct destruction with lymphocytic infiltration.

Lab tests:

- Elevated ALP, GGT; mild ALT/AST rise.

- Hyperbilirubinemia in advanced stages.

- AMA-M2 most specific; also anti-gp210, anti-sp100 antibodies indicate poor prognosis.

- Lipid abnormalities (high cholesterol).

Imaging: Ultrasound rules out obstruction; MRCP or biopsy confirms.

Differential diagnosis:

| Condition | Key Distinctions |

|---|---|

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | Extrahepatic ducts involved; p-ANCA positive; more in men. |

| Biliary obstruction | Normal AMA; dilated ducts on imaging. |

| Drug-induced liver injury | History of exposure; resolves post-discontinuation. |

| Viral hepatitis | Hepatitis serologies positive. |

Treatment and Management

No cure exists, but treatments slow progression and manage symptoms.

First-line: Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) (13-15 mg/kg/day): Improves bile flow, reduces ALP/bilirubin. 2/3 respond biochemically; non-responders risk progression.

Second-line for inadequate UDCA response:

- Obeticholic acid (OCA): Farnesoid X receptor agonist; lowers ALP. FDA-approved 2016 for non-responders.

- Fibrates (bezafibrate, fenofibrate): PPAR agonists; off-label, reduce cholestasis markers.

Symptom management:

- Pruritus: Cholestyramine, rifampin, naltrexone, sertraline.

- Fatigue: Modafinil (limited evidence).

- Vitamin supplementation: Fat-soluble vitamins.

- Osteoporosis: Bisphosphonates, calcium, vitamin D.

Advanced disease: Liver transplant offers excellent outcomes; recurrence possible but rare.

Prognosis and Complications

With UDCA, many achieve stable disease; poor prognostic factors: high bilirubin, poor UDCA response, advanced histology.

Bilirubin-based survival:

- >2 mg/dL: ~4 years.

- >6 mg/dL: ~2 years.

- >10 mg/dL: ~1.4 years.

Mayo Risk Score predicts transplant-free survival. Fatigue correlates with worse outcomes.

Complications: Cirrhosis (20-50%), hepatocellular carcinoma (linked to cirrhosis), osteoporosis (high prevalence).

Living with Primary Biliary Cholangitis

Patients should monitor liver function regularly, adhere to therapy, avoid alcohol/toxins, eat low-fat diets rich in vitamins, and exercise to combat fatigue/osteoporosis. Support groups aid coping; early detection improves outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the main cause of primary biliary cholangitis?

PBC results from genetic susceptibility triggered by environmental factors like infections or toxins, leading to an autoimmune attack on bile ducts.

Is PBC curable?

No, but UDCA and other therapies slow progression; liver transplant treats end-stage disease.

How is PBC diagnosed?

By elevated ALP, positive AMA, and/or biopsy confirming bile duct damage.

What are common early symptoms of PBC?

Fatigue and pruritus; many are asymptomatic initially.

Who is at risk for PBC?

Middle-aged women with family history; genetic and environmental factors play roles.

References

- Primary Biliary Cholangitis – StatPearls — Kaplan, G.G., et al. 2023-10-01. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459209/

- Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Medical and Specialty Pharmacy Management — Bowlus, C.L., et al. 2016-10-01. https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.10-a-s.s3

- Primary Biliary Cholangitis – Cholestasis Unveiled — Springer Healthcare. 2023-01-01. https://rare-liver-disorders.ime.springerhealthcare.com/2-primary-biliary-cholangitis/

Read full bio of medha deb