Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum Pathology

Comprehensive pathology of pseudoxanthoma elasticum: skin, eye, vascular changes and diagnostic criteria.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) is a rare, inherited multisystem disorder characterized by progressive calcification and fragmentation of elastic fibers in the skin, eyes, and cardiovascular system. This pathology leads to distinctive clinical manifestations, with skin changes often being the earliest sign.

Introduction

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum, abbreviated as PXE, represents an ectopic mineralization disorder primarily affecting elastic tissues. It is an autosomal recessive condition caused predominantly by mutations in the ABCC6 gene, resulting in defective transport of anti-mineralization factors. The disease manifests in the second or third decade of life, with skin lesions serving as a hallmark for diagnosis, often preceding more severe ocular and vascular complications.

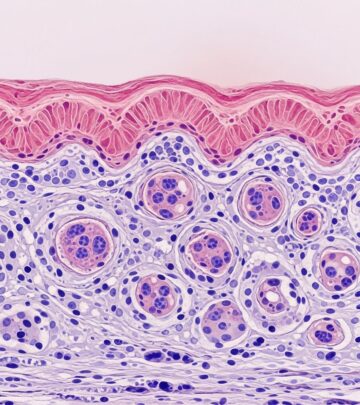

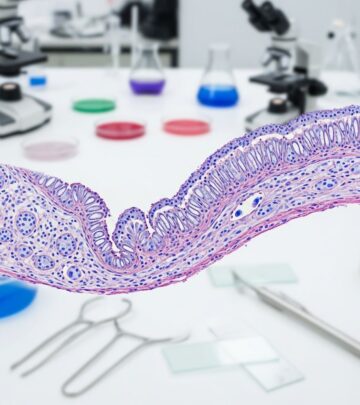

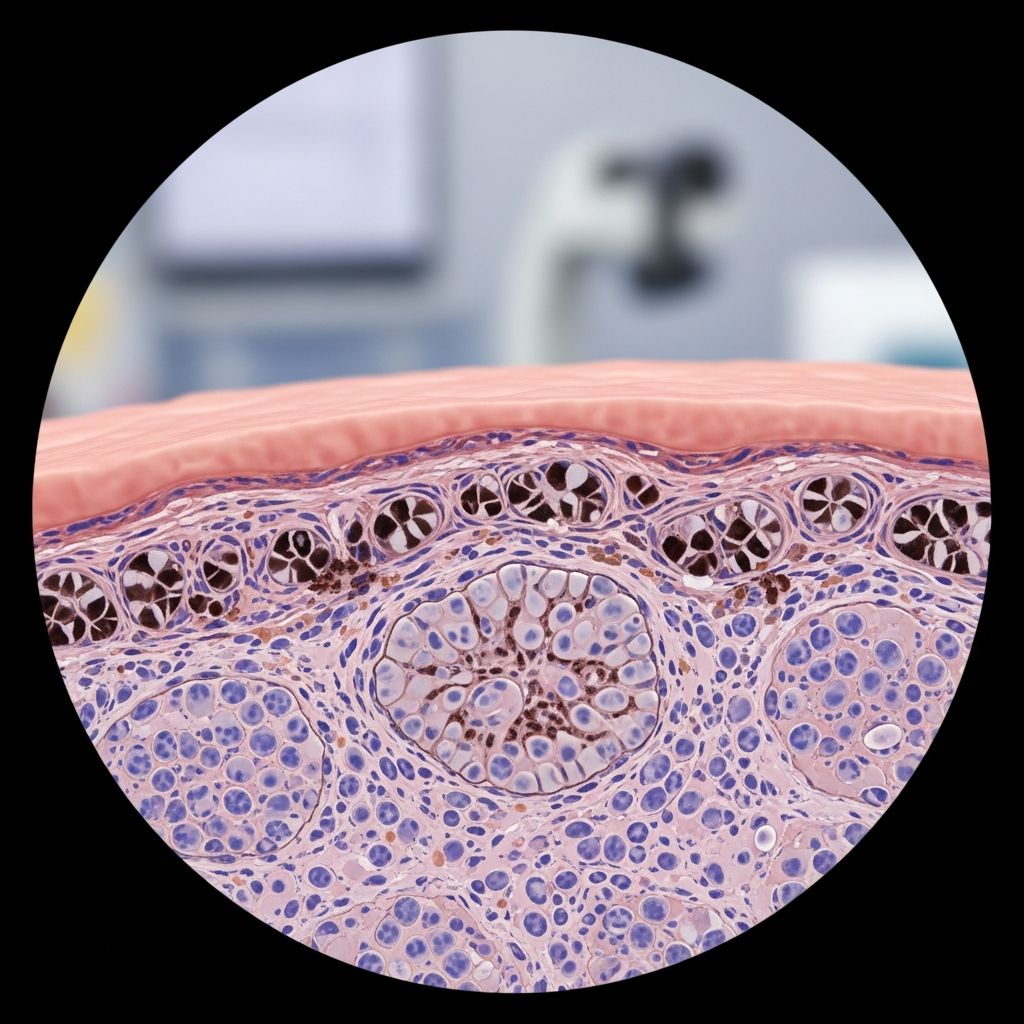

Histopathologically, PXE is defined by the accumulation of pleomorphic, mineralized elastic structures in the mid- and lower dermis, confirmed by calcium-specific stains. While skin biopsies provide definitive evidence, genetic testing for biallelic ABCC6 mutations confirms the diagnosis in most cases.

Clinical Features

The clinical presentation of PXE varies but follows a predictable pattern affecting skin, eyes, and vasculature. Early recognition is crucial to monitor for vision loss and cardiovascular events.

Skin Manifestations

Skin changes are the most common initial feature, appearing as small, yellowish papules on predilection sites such as the lateral neck, axillae, antecubital and popliteal fossae. These papules coalesce into leathery, inelastic plaques with a cobblestone or plucked chicken appearance, leading to redundant, lax skin. While primarily cosmetic, these lesions signal potential systemic involvement.

- Predilection sites: Neck, axillae, cubital fossae, groin, periumbilical area.

- Progression: Papules plaques cutaneous laxity and redundancy.

- Histological correlation: Essential for diagnosis when clinical suspicion exists.

Ocular Manifestations

Ocular involvement affects over 80% of patients, with peau d’orange (mottled hyperpigmentation in the temporal retina) appearing first, often in adolescence. This precedes angioid streakscrack-like ruptures in the calcified Bruch’s membranewhich can lead to choroidal neovascularization, subretinal hemorrhage, and central vision loss. Fundoscopy, fluorescein angiography, and OCT are key diagnostics.

- Peau d’orange: Early sign due to Bruch’s membrane calcification.

- Angioid streaks: Pathognomonic, >1 disc diameter in size.

- Complications: Visual acuity loss, comet-tail chorioretinal atrophy.

Cardiovascular and Other Manifestations

Vascular complications include premature atherosclerosis, peripheral artery disease, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage from angiodysplasia. Rare associations include mitral valve prolapse and hypertension. ENPP1-associated variants present with severe early arterial calcification.

| System | Common Findings | Severity |

|---|---|---|

| Skin | Yellowish papules/plaques | Cosmetic mainly |

| Eyes | Angioid streaks, vision loss | High morbidity |

| Vascular | Atherosclerosis, GI bleed | Potentially fatal |

Histopathology

Skin biopsy from lesional or perilesional areas is cornerstone for diagnosis. Routine haematoxylin and eosin (HHE) staining reveals swollen, clumped elastic fibers in the mid- and lower dermis. Verhoeff-Van Gieson stain highlights fragmented, shortened elastica, while von Kossa or Alizarin red confirms calcium deposition.

- HHE: Basophilic elastic fiber aggregates resembling xanthomas.

- Elastic stains: Irregular, broken fibers with granular material.

- Calcium stains: Black (von Kossa) or red (Alizarin) deposits on fibers.

- Electron microscopy: Electrodense deposits within elastic lamellae.

Collagen fibers may show deformation, and in advanced cases, perforating channels akin to elastosis perforans serpiginosa can occur.

Pathogenesis

PXE exemplifies a paradigm of ectopic mineralization due to loss-of-function in ABCC6, an ATP-binding cassette transporter in liver/kidney. This impairs pyrophosphate (PPi) export, a key mineralization inhibitor, leading to elevated tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase activity and elastic fiber calcification.

Variants like ENPP1 mutations cause generalized arterial calcification of infancy (GACI), overlapping with PXE spectrum. Mouse models (Abcc6-/-) recapitulate the phenotype, confirming the mechanism.

Genetics

Classic PXE is autosomal recessive, linked to chromosome 16p13.1 (ABCC6). Over 400 mutations identified, mostly nonsense or frameshift leading to absent protein. Genetic testing detects mutations in ~95% of probands. Rare dominant forms exist with milder phenotypes.

Diagnostic Criteria

Definitive diagnosis requires combination of clinical, histopathological, and genetic findings. Consensus criteria include:

| Category | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Definitive PXE | Two pathogenic ABCC6 mutations OR ocular findings (angioid streaks >1 DD or peau d’orange <20yo) + skin findings/biopsy |

| Provisional | One major criterion + suggestive findings; repeat evaluation |

Biopsy from neck/flexures even without visible lesions; exclude mimics like amyloidosis or lipoid proteinosis.

Differential Diagnosis

- Elastosis perforans serpiginosa

- Schönlein-Henoch purpura (early lesions)

- Other mineralization disorders (GACI, beta-thalassemia)

- Angioid streaks mimics: Paget disease, sickle cell

Management and Prognosis

No cure; management is symptomatic. Skin: cosmetic surgery. Ocular: anti-VEGF for neovascularization, low-vision aids. Vascular: antiplatelets, statins, avoid trauma. Genetic counseling essential. Prognosis guarded due to vision/cardiac risks.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What causes pseudoxanthoma elasticum?

A: Primarily biallelic mutations in ABCC6 gene, leading to elastic fiber mineralization.

Q: How is PXE diagnosed?

A: Combination of skin biopsy showing calcified elastic fibers, ocular angioid streaks, and genetic testing.

Q: Can PXE be treated?

A: No cure; supportive care targets complications like vision loss and vascular disease.

Q: Is PXE hereditary?

A: Yes, autosomal recessive inheritance; carrier screening recommended for families.

Q: What are the first signs of PXE?

A: Yellowish papules on neck or flexures, often in teens/20s.

Conclusion

PXE pathology underscores the importance of elastic tissue integrity. Early diagnosis via histopathology and genetics enables proactive management to mitigate morbidity.

References

- Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: diagnostic features, classification, and treatment options Uitto J, et al. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs. 2014-06-01. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4219573/

- Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum EyeWiki (AAO). Last updated 2023. https://eyewiki.org/Pseudoxanthoma_Elasticum

- Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum (PXE) DermNet NZ. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/pseudoxanthoma-elasticum

- Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum NORD (Rare Diseases). Updated 2023. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/pseudoxanthoma-elasticum-pxe/

- Pseudoxanthoma elasticum Autopsy and Case Reports. 2017. https://www.autopsyandcasereports.org/article/10.4322/acr.2017.035/pdf/autopsy-7-4-18.pdf

Read full bio of Sneha Tete