Severe Combined Immunodeficiency: Diagnosis and Treatment

Understanding SCID: Early diagnosis and advanced treatments offer hope for children with this rare immune disorder.

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID)

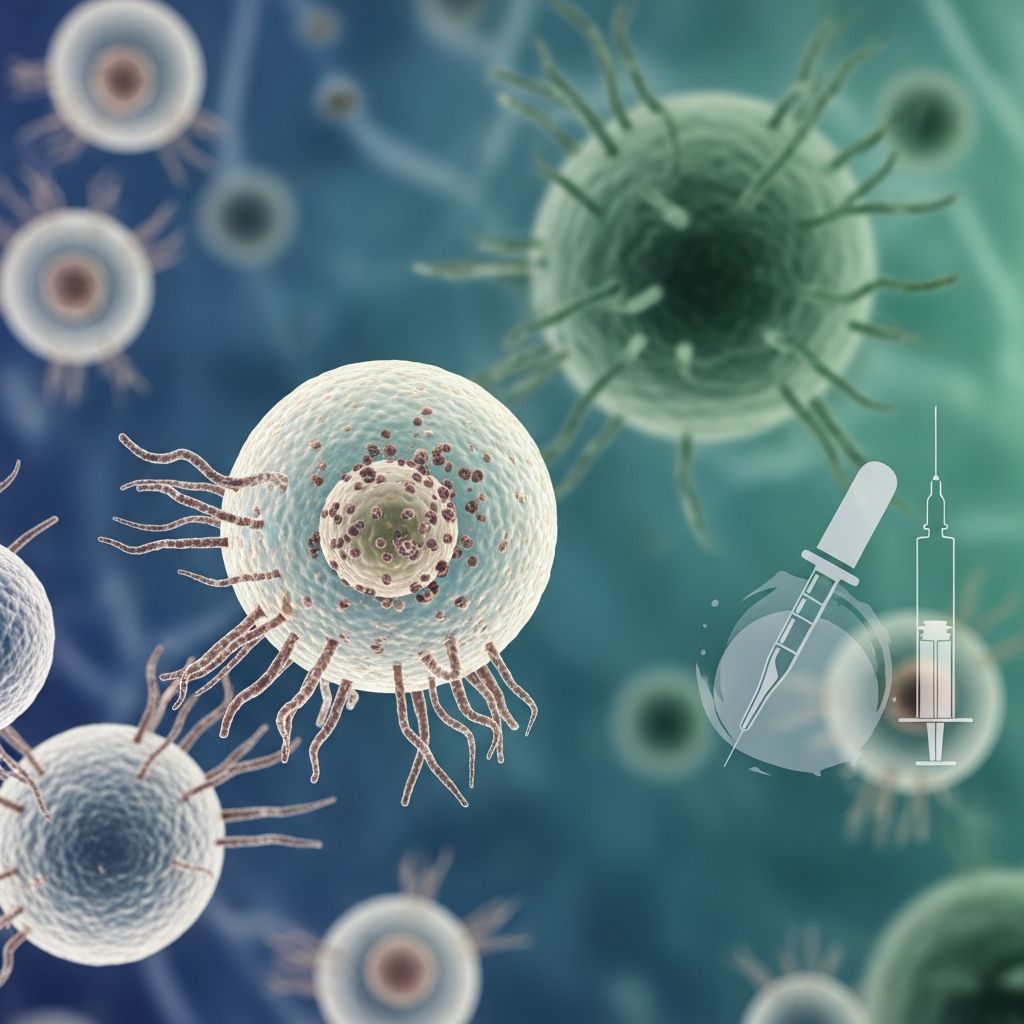

Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) represents a group of rare, inherited immune system disorders characterized by the profound loss or dysfunction of T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, and natural killer cells. This critical combination of immune deficiencies leaves affected individuals—predominantly infants and young children—extremely vulnerable to life-threatening infections. Without prompt intervention, SCID constitutes a pediatric emergency, as children typically do not survive beyond their first year of life.

The condition manifests through the body’s inability to produce functional lymphocytes needed to fight infections. All forms of classic SCID are lethal unless treated appropriately. However, advances in newborn screening, early diagnosis, and sophisticated treatment modalities have dramatically transformed the outlook for children with SCID, with many now achieving successful immune system reconstruction and normal lifespans.

Types of SCID

SCID encompasses several distinct genetic subtypes, each resulting from different defects in immune cell development. Understanding these classifications helps guide treatment decisions and prognosis.

T-Cell-Negative Forms

The most common forms of SCID involve absent or severely reduced T cell numbers. These include adenosine deaminase (ADA) SCID, caused by deficiency of the ADA enzyme critical for T cell survival, and IL2RG SCID, an X-linked form resulting from defects in the common gamma chain receptor. These variants account for the majority of SCID cases and represent particularly severe presentations of the disease.

T-B+ NK+ SCID

This form presents with selective defects in T cell development while preserving B and natural killer cells. The deficiency arises from either loss of a cytokine or growth factor receptor or T cell antigen receptor abnormalities, both essential for proper T cell maturation and survival. Despite preservation of other lymphocyte populations, affected children remain profoundly immunocompromised.

Other Genetic Variants

Additional rare forms of SCID include RAG1/RAG2 deficiencies, PNP deficiency, and other genetic mutations affecting lymphocyte development. Each variant presents unique challenges and may respond differently to therapeutic interventions.

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms

Children with SCID typically present with recurrent, severe, and persistent infections that fail to respond to standard treatment protocols. The pattern and severity of infections often provide critical diagnostic clues.

Common Presenting Infections

- Pneumonia and recurrent lower respiratory tract infections

- Meningitis and serious central nervous system infections

- Sepsis and bloodstream infections

- Chronic diarrhea, often persistent and difficult to treat

- Oral thrush and persistent yeast infections

- Chronic skin infections and dermatological complications

- Recurrent ear infections

Warning Signs Requiring Urgent Evaluation

- Infections that do not resolve with two months of antibiotic treatment

- Infections requiring intravenous antibiotic therapy

- Eight or more persistent ear infections annually

- Persistent thrush in the mouth or throat

- Repeated cases of pneumonia or bronchitis

- Failure to thrive or gain weight appropriately

- Deep infections affecting entire organs such as lungs or liver

- Family history of immunodeficiency or unexplained infant deaths from infections

Additional symptoms may include red and peeling skin, hair loss (alopecia), enlarged lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), and hepatosplenomegaly (enlarged liver and spleen). The constellation of these clinical features warrants immediate immunological evaluation.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Early diagnosis is critical for improving outcomes. The diagnostic approach combines clinical assessment with specialized laboratory investigations to confirm the diagnosis and identify the specific genetic defect.

Initial Assessment

Diagnosis typically begins with a comprehensive medical history, detailed family history, and thorough physical examination. Particular attention is paid to identifying recurrent or atypical infections and evaluating for physical stigmata associated with SCID.

Laboratory Testing

Multiple blood tests are ordered to confirm SCID diagnosis and identify the underlying genetic defect. These investigations include:

- Complete blood count to assess lymphocyte populations

- T cell enumeration and function studies

- B cell and NK cell assessment

- Immunoglobulin levels

- Lymphocyte proliferation assays

- Genetic testing to identify specific mutations

Newborn Screening

Modern newborn screening programs in many states now detect SCID through T cell receptor excision circle (TREC) analysis before clinical symptoms develop. This represents a paradigm shift in SCID management, allowing for presymptomatic diagnosis and early intervention before life-threatening infections occur. Early identification dramatically improves survival rates and reduces morbidity.

Treatment Options

Treatment for SCID requires a coordinated, multidisciplinary approach addressing immediate infection management, immune system restoration, and long-term immune reconstitution. Timing and early intervention are critical—the sooner treatment begins, the less likely children will contract fatal infections.

Supportive Care

While definitive treatment is pursued, supportive measures prevent opportunistic infections and manage current illness:

- Antibiotics: Used to treat active infections and prevent new infections

- Antivirals and antifungals: Guard against viral and fungal pathogens

- Immunoglobulin replacement (IVIG): Intravenous immune globulin provides passive immunity and antibody support

- Infection prevention: Restricted contact with other people and strict hygiene protocols minimize exposure to new pathogens

- Enzyme infusions: Depending on the underlying genetic defect, enzyme replacement therapy may be initiated

Bone Marrow Transplant

The most effective and commonly used treatment for SCID is bone marrow transplantation, also referred to as stem cell transplantation. This procedure involves transplanting healthy blood-forming stem cells from a matched donor into the child after conditioning therapy has eliminated diseased marrow.

Transplant Process

Conditioning therapy represents the first critical step, involving chemotherapy and sometimes radiation to destroy the unhealthy bone marrow and create space for new, healthy donor cells. Following conditioning, healthy donor cells are delivered through an intravenous catheter in a process called stem cell infusion. These cells travel to the bone cavity and begin producing new, functional blood cells and immune cells.

Donor Sources

The best outcome occurs when a matched sibling donor is available—less than one in four children with SCID possess this advantage. When a matched family donor is unavailable, the National Marrow Donor Program maintains a registry of unrelated donors. Careful matching is essential for transplant success and to minimize complications such as graft-versus-host disease.

Success Rates

Bone marrow and stem cell transplantation achieve cure rates as high as 80% for SCID patients. Children receiving early transplants, particularly those diagnosed through newborn screening before symptom onset, experience significantly improved outcomes and higher survival rates. The new donor cells successfully rebuild the immune system, allowing children to develop normal infection-fighting capabilities.

Advanced Treatment Modalities

Gene Therapy

Gene therapy represents a promising frontier in SCID treatment, offering new hope for patients who have not achieved cure following bone marrow transplantation. This experimental approach involves removing the patient’s bone marrow stem cells, introducing a corrected copy of the defective gene into these cells, and then reinfusing the genetically modified cells into the patient’s body.

In the United States, gene therapy for SCID currently remains available exclusively through clinical trials. Active research studies target specific SCID subtypes, including IL2RG and DLRE1C (Artemis) forms. In Europe, gene therapy has achieved commercial availability for ADA SCID, with hopes for future U.S. approval. This represents a significant advance, as gene therapy offers an alternative pathway to immune reconstitution without requiring a matched donor.

Enzyme Replacement Therapy

For children with ADA SCID specifically, enzyme replacement therapy offers a treatment option by providing the deficient adenosine deaminase enzyme through regular injections. This approach allows cells within the body to recover and begin combating infections more effectively. While enzyme therapy is a treatment rather than a cure, it provides long-term benefits for some children and may serve as a bridge therapy while awaiting transplant or as an alternative for those who cannot tolerate transplantation.

Multidisciplinary Team Approach

Optimal SCID management requires coordination among multiple medical specialists working together to develop individualized treatment plans addressing each child’s unique needs. Essential team members typically include:

- Immunologists specializing in immune system disorders

- Geneticists providing genetic counseling and interpretation

- Transplant physicians overseeing stem cell transplantation

- Infectious disease specialists managing current and preventing future infections

- Hematologists monitoring blood and bone marrow function

- Pediatric specialists providing general medical care

- Nursing and support staff ensuring comprehensive care coordination

Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

Without appropriate treatment, SCID remains uniformly fatal, with most untreated children not surviving beyond their first year of life. However, modern therapeutic approaches have revolutionized the prognosis. Early diagnosis through newborn screening, prompt initiation of treatment, and bone marrow transplantation in optimal timing windows now result in survival rates exceeding 80%.

Children who successfully undergo early stem cell transplantation may achieve complete immune reconstitution and live normal lifespans. Even children diagnosed after symptom onset can benefit from transplantation and other advanced therapies, though outcomes correlate strongly with the timing of diagnosis and treatment initiation.

Long-term follow-up care remains essential to monitor for potential complications, ensure ongoing immune system function, and manage any late effects of transplantation or other therapies. Many successfully treated SCID patients attend school, participate in normal activities, and achieve independence as adults.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the difference between SCID and other immunodeficiency disorders?

A: SCID is distinguished by deficiencies in multiple immune cell populations simultaneously (T cells, B cells, and NK cells), whereas other immunodeficiencies may affect single cell types. This combined deficiency creates the profound immunosuppression characteristic of SCID.

Q: Can SCID be prevented through prenatal testing?

A: Prenatal genetic testing can identify SCID in families with known genetic mutations, enabling families to make informed reproductive decisions. Early identification allows for immediate postnatal treatment planning.

Q: How long does bone marrow transplant recovery take?

A: Initial immune recovery occurs over months following transplantation, though complete immune reconstitution may take years. Most protective immunity develops within 6-12 months post-transplant.

Q: What are the risks of bone marrow transplantation for SCID?

A: Potential complications include graft-versus-host disease, graft rejection, infection during the conditioning period, and secondary malignancies. However, the benefits of immune reconstitution typically outweigh these risks.

Q: Will my child need lifelong medication after treatment?

A: Successfully transplanted children gradually reduce and often discontinue immunosuppressive medications as their new immune system becomes established. However, long-term monitoring and preventive care remain important.

References

- Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) — Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. 2024. https://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/severe-combined-immunodeficiency-scid

- Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) — St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. 2024. https://www.stjude.org/care-treatment/treatment/immune-disorders/immunodeficiency-disease/severe-combined-immunodeficiency-scid.html

- Severe Combined Immunodeficiency – Symptoms, Causes, Treatment — National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD). 2024. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/severe-combined-immunodeficiency/

- Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) Treatment — National Marrow Donor Program. 2024. https://www.nmdp.org/patients/understanding-transplant/diseases-treated-by-transplant/severe-combined-immunodeficiency

- Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) — St. Louis Children’s Hospital. 2024. https://www.stlouischildrens.org/conditions-treatments/severe-combined-immunodeficiency-scid

- Severe Combined Immunodeficiency — National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK22254/

Read full bio of Sneha Tete