Syphilis Pathology

Detailed histopathological examination of syphilis across primary, secondary, and tertiary stages, highlighting key microscopic features and diagnostic stains.

Syphilis is a chronic infectious disease caused by the spirochaete Treponema pallidum, a delicate spiral-shaped bacterium that invades skin and mucous membranes primarily through sexual contact or vertical transmission. The histopathological features of syphilis vary significantly across its stages—primary, secondary, and tertiary—reflecting the evolving immune response and tissue damage. Understanding these microscopic changes is crucial for dermatopathologists, as syphilis mimics many other conditions and requires correlation with clinical findings and serology for definitive diagnosis. This article delves into the characteristic histological patterns, special stains, and diagnostic pitfalls, drawing from authoritative sources to provide a thorough reference.

Authoritative Facts

- Syphilis pathology demonstrates stage-specific changes: acanthosis and ulceration in primary lesions, psoriasiform hyperplasia in secondary, and granulomatous inflammation in tertiary.

- T. pallidum organisms are numerous in early stages but scarce in late disease, best visualized with immunohistochemistry or silver stains.

- Plasma cells and endothelial swelling are hallmark dermal features across stages, aiding in suspicion of treponemal infection.

Histology of Syphilis

The histological diagnosis of syphilis hinges on recognizing subtle yet distinctive patterns in tissue samples from lesional biopsies. T. pallidum elicits a robust inflammatory response characterized by lymphocytic infiltrates, plasma cells, and vascular changes. Early lesions teem with spirochetes, while late stages show fewer organisms amid destructive inflammation. Clinical context—such as a painless genital ulcer or symmetric rash—is essential, as morphology alone can overlap with psoriasis, lichen planus, or granulomatous diseases.

Primary Syphilis (Primary Chancre)

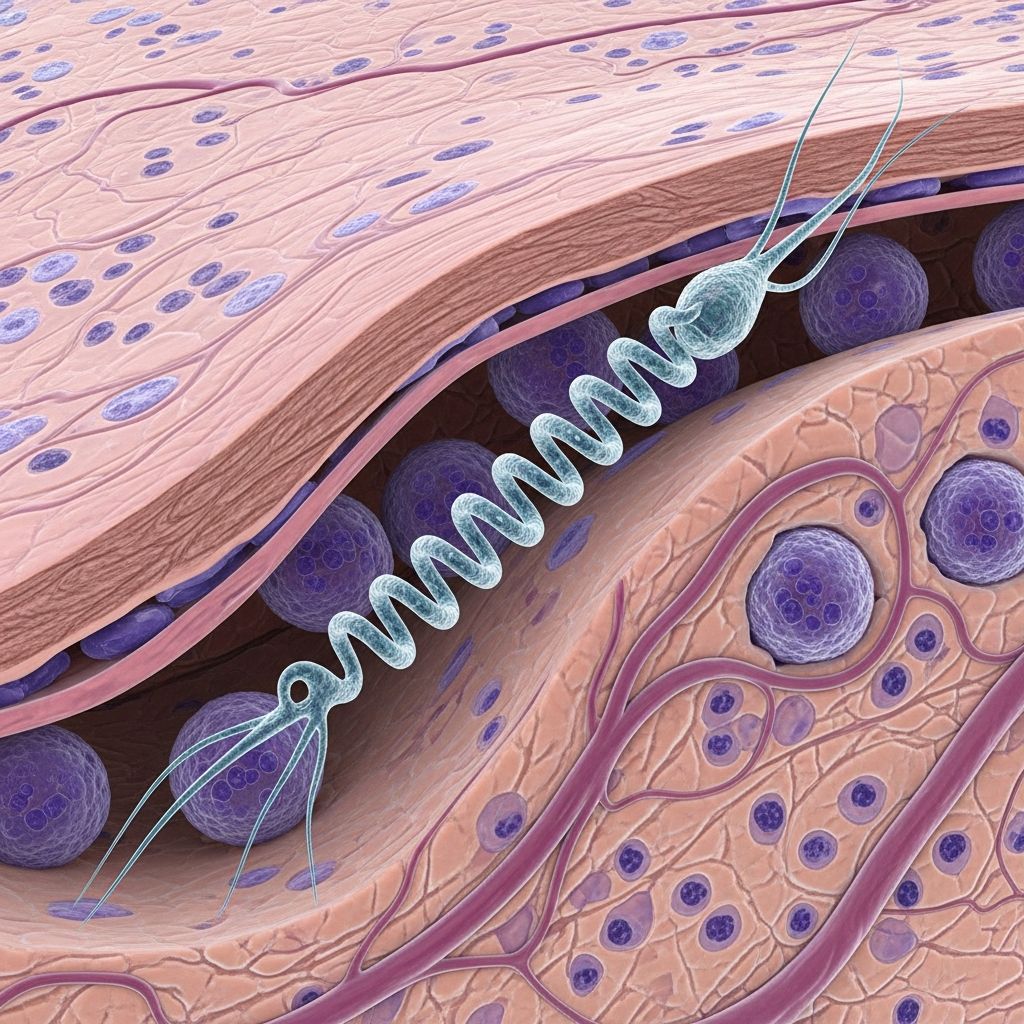

Primary syphilis manifests as a painless chancre at the inoculation site, typically 10–90 days post-exposure (average 21 days). Histologically, the epidermis shows acanthotic hyperplasia early on, progressing to erosion and ulceration as the spirochete penetrates the basal layer using its corkscrew motility. Beneath the ulcer bed lies a dense, band-like infiltrate of lymphocytes and numerous plasma cells, with prominent endothelial swelling in dermal vessels—a classic triad pointing to treponemal infection.

Magnification reveals spiral-shaped organisms clustering around vessels and at the epidermo-dermal junction, often highlighted by immunohistochemistry (IHC) against T. pallidum antigens (e.g., Tp47 or PolA). Warthin-Starry silver stain also delineates the spirochetes as thin, tightly coiled filaments. The chancre resolves spontaneously in 4–8 weeks without scarring, but untreated infection disseminates systemically. Differential diagnoses include herpes simplex (multinucleated keratinocytes absent here) and chancroid (more suppuration).

Secondary Syphilis

Secondary syphilis arises 3–12 weeks after the primary chancre due to hematogenous spread, presenting with a symmetric maculopapular rash on trunk, palms, and soles, plus constitutional symptoms like fever and lymphadenopathy. Histopathology exhibits marked variability, often mimicking other dermatoses, which earns syphilis its moniker “the great imitator”.

The epidermis frequently displays psoriasiform hyperplasia with elongated rete ridges, parakeratosis, and superficial neutrophilic collections (munro microabscesses). A lichenoid interface reaction features basal vacuolization, apoptotic keratinocytes, and exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils into the epidermis. The dermis harbors a superficial and deep perivascular infiltrate rich in lymphocytes, with plasma cells in about one-third of cases and endothelial swelling.

Less common patterns include eczematous spongiosis, folliculitis, pustules, or acantholysis, underscoring the need for special stains. Spirochetes are plentiful, coiled around vessels and appendages, visible via IHC or PCR targeting genes like polA or tpp47. Resolution occurs over weeks, but relapses are common without treatment.

Tertiary Syphilis

Tertiary syphilis develops years after latency, affecting skin, bones, cardiovascular system, or CNS as gummas—necrotizing granulomatous lesions. Skin gummas show necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with central caseous necrosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes, multinucleate giants, and lymphocytes. Fibrosis and vascular occlusion contribute to tissue destruction.

Spirochetes are rare and difficult to detect with routine stains, necessitating clinical correlation. Plasma cells may persist, but the dominant feature is granuloma formation, mimicking tuberculosis or deep fungal infections. Neurosyphilis can occur anytime, with PCR on CSF aiding diagnosis.

Special Stains and Diagnostic Techniques

Direct visualization of T. pallidum confirms infection, especially in early stages when organisms abound.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Gold standard; polyclonal antibodies against T. pallidum reveal spiral forms with high sensitivity/specificity.

- Warthin-Starry/Steiner Silver Stains: Highlight spirochetes as black coils on gold background; useful but less specific.

- Dark-Field Microscopy: Rapid bedside detection of motile spirochetes from exudate; limited availability.

- PCR: Targets polA, tpp47, tmpA; ideal for formalin-fixed tissue or mucosal sites.

- Electron Microscopy: Rarely used; confirms ultrastructure.

Serology complements histology: treponemal tests (FTA-ABS, TPPA) confirm exposure; nontreponemal (RPR/VDRL) gauge activity and treatment response. Prozone phenomenon can cause false-negatives in high-titer secondary disease.

Diagnostic Pitfalls and Clinical Correlation

Syphilis histology is protean: secondary lesions may resemble pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, or lichenoid drug eruptions. Plasma cells + endothelial swelling + psoriasiform epidermis should prompt treponemal testing. In HIV patients, presentations are atypical with more aggressive courses. Always integrate serology, history (high-risk exposure), and follow-up titers.

| Stage | Key Epidermal Changes | Dermal Infiltrate | Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Acanthosis → Ulcer | Lymphocytes, plasma cells, endothelial swelling | Numerous |

| Secondary | Psoriasiform, apoptosis, neutrophils | Superficial/deep perivascular, plasma cells (1/3) | Numerous |

| Tertiary | Variable atrophy/granuloma | Necrotizing granulomas | Rare |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the hallmark histological feature of primary syphilis?

A dense plasma cell-rich infiltrate with endothelial swelling beneath an ulcerated epidermis.

How reliable is IHC for detecting T. pallidum?

Highly sensitive and specific, superior to silver stains for spiral morphology.

Why might secondary syphilis be histologically variable?

Reflects diverse immune responses, mimicking eczema, granulomas, or folliculitis.

Can syphilis be diagnosed without seeing organisms?

Yes, via suggestive histology + positive serology; organisms scarce in tertiary disease.

What PCR targets confirm T. pallidum?

polA, tpp47, tmpA; validated for lesion swabs and FFPE tissue.

References

- Syphilis – DermNet — DermNet NZ. 2023-06-01. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/syphilis

- Syphilis Pathology – DermNet — DermNet NZ. 2023-06-01. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/syphilis-pathology

- The Laboratory Diagnosis of Syphilis — National Library of Medicine (PMC). 2021-09-20. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8451404/

- Syphilis: Testing for the Great Imitator — BPAC NZ. 2012-06-01. https://bpac.org.nz/BT/2012/June/06_syphilis.aspx

- PCR Swabs: A Useful Diagnostic Tool for Identifying Syphilis — This Changed My Practice. 2023-01-15. https://thischangedmypractice.com/pcr-swabs-diagnostic-tool-identifying-syphilis/

Read full bio of Sneha Tete