Tendons: Structure, Function & Health

Understanding tendons: The connective tissues that link muscles to bones and enable movement.

What Are Tendons?

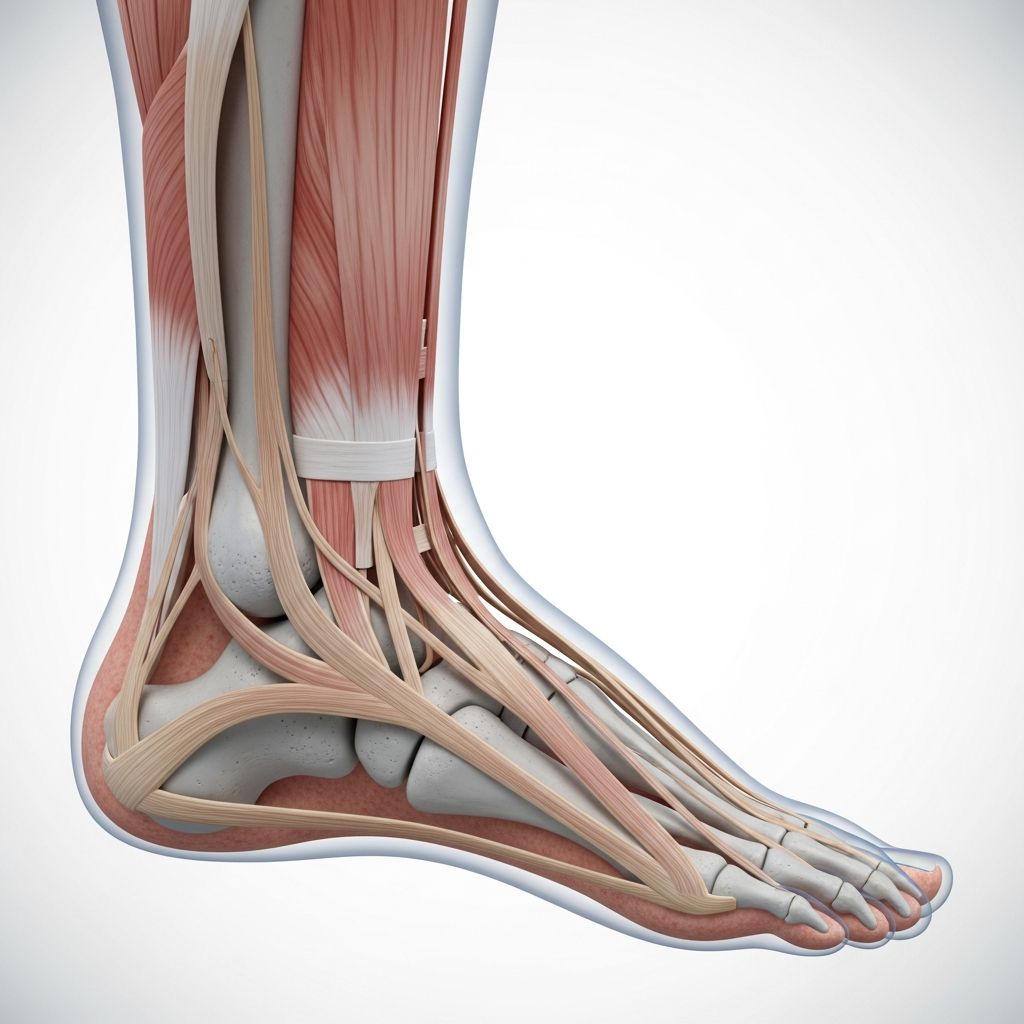

Tendons are the connective tissues that transmit the mechanical force of muscle contraction to the bones, enabling movement throughout your body. They are firmly connected to muscle fibers at one end and to components of the bone at the other end, serving as the critical link between your muscles and skeletal system. When you contract a muscle, its tendons pull the attached bone, making it move—much like levers that help bones respond when your muscles contract and expand. Without tendons, your muscles would be unable to produce the movements necessary for everyday activities like walking, lifting, and reaching.

Tendons are remarkably strong, possessing one of the highest tensile strengths found among soft tissues. This exceptional strength is necessary for withstanding the stresses generated by muscular contraction and is attributed to the hierarchical structure, parallel orientation, and specific tissue composition of tendon fibers. Despite their strength, tendons are also flexible and can stretch slightly, allowing them to absorb shock and accommodate the dynamic movements required by your body.

Tendon Structure and Composition

Understanding the anatomy of tendons reveals why they are so effective at their job. A tendon is composed of dense fibrous connective tissue made up primarily of collagenous fibers. The hierarchical organization of these fibers is key to the tendon’s function and strength.

Organizational Hierarchy

Tendons are organized in a precise hierarchical structure. Primary collagen fibers, which consist of bunches of collagen fibrils, are the basic units of a tendon. These primary fibers are bunched together into primary fiber bundles, also called subfascicles. Groups of primary bundles form secondary fiber bundles, known as fascicles. Multiple secondary fiber bundles then form tertiary fiber bundles, and groups of tertiary bundles together make up the complete tendon unit. This layered architecture distributes stress evenly across the tissue and maximizes tensile strength.

Supporting Tissues

Each level of the tendon hierarchy is surrounded by specialized connective tissue sheaths that facilitate movement and reduce friction. Primary, secondary, and tertiary bundles are surrounded by a sheath of connective tissue known as endotenon, which allows the bundles to glide against one another during tendon movement. The endotenon is continuous with the epitenon, a fine layer of connective tissue that sheaths the entire tendon unit. Outside the epitenon lies the paratenon, a loose elastic connective tissue layer that allows the tendon to move against neighboring tissues without restriction.

Bone Attachment

At its point of attachment to bone, the tendon is connected through specialized collagenous fibers called Sharpey fibers that continue into the matrix of the bone. This creates a seamless transition between the soft tissue of the tendon and the hard tissue of bone, ensuring secure attachment and efficient force transmission.

Tendon Composition and Proteins

The strength and elasticity of tendons come from their specific protein composition. Tendons are made primarily of two types of proteins: collagen and elastin. Collagen is the most common protein in your body, comprising around one-third of your body’s total protein. It provides the primary strength and structural integrity to tendons, giving them their remarkable tensile strength. Elastin, on the other hand, is stretchy and helps your tendons extend and bounce back to their original shapes as you move. This combination of proteins allows tendons to be both strong and resilient, capable of handling repeated stress while maintaining their flexibility.

Tendon Cells

The primary cell types within tendons are specialized cells that maintain and produce the tissue structure. The main cell types are spindle-shaped tenocytes (fibrocytes) and tenoblasts (fibroblasts). Tenocytes are mature tendon cells found throughout the tendon structure, typically anchored to collagen fibers, and they maintain the tendon’s function. Tenoblasts are spindle-shaped immature tendon cells that give rise to tenocytes. These tenoblasts typically occur in clusters free from collagen fibers and are highly proliferative, meaning they actively divide and are involved in the synthesis of collagen and other components of the extracellular matrix. This cellular activity is crucial for tendon repair and adaptation to increased demands.

Types of Tendons in Your Body

The Achilles Tendon

The Achilles tendon is the thickest and strongest tendon in your body, connecting your calf muscles to your heel bone (calcaneus). Located at the back of your leg right above your ankle, the Achilles tendon usually measures between 6 and 10 inches (15 to 26 centimeters) long in adults and can support forces around four times your body weight. This remarkable strength is necessary because the Achilles tendon bears significant load during activities like walking, running, jumping, and climbing stairs. The Achilles tendon gets its name from Achilles, a hero in ancient Greek mythology who was invulnerable to any injuries except for one spot on the back of his heel—a reference that has made the Achilles tendon metaphorically famous in medical terminology.

Hand and Wrist Tendons

Your hand and wrist contain numerous tendons that provide the fine motor control necessary for precise movements. These tendons link your muscles to your bones and function like strong, flexible ropes. The hand and wrist have two main groups of tendons that work together to provide strength and dexterity. Nine tendons pass through the carpal tunnel, a rounded space in your wrist that acts like a tunnel allowing these tendons, along with four ligaments and one nerve, to reach the rest of your hand. This compact arrangement is similar to fiber optic cables buried underground to deliver internet or cable services.

Rotator Cuff Tendons

The rotator cuff is a group of muscles and tendons around your shoulder joint that helps you move and rotate your arm and shoulder. These tendons connect the muscles in your rotator cuff to the bones around them, functioning as levers that move your bones as your muscles contract and expand. When you contract muscles in your rotator cuff, the tendons pull the attached bones to move your shoulder and upper arm, enabling the full range of shoulder motion.

How Tendons Work

Tendons function as the essential link in the muscle-bone system. When you decide to move a body part, your nervous system sends a message to the appropriate muscles. The muscles contract, shortening and creating tension. This tension is transmitted through the tendons to the bones, causing them to move at the joints. The tendons essentially act as mechanical levers, converting the pulling force of muscle contraction into bone movement. To relax the muscle and reverse the movement, your nervous system sends another message that triggers the muscle to return to its resting state.

The blood supply and nerve supply to tendons are equally important for their function. For example, the Achilles tendon gets blood from two blood vessels in your lower leg, ensuring it receives adequate oxygen and nutrients for repair and maintenance. Two nerves—the sural nerve and tibial nerve—control the Achilles tendon and give it sensation. This nerve supply allows your body to sense the position and tension of the tendon, providing proprioceptive feedback that helps coordinate movement.

Common Tendon Injuries and Conditions

Tendonitis (Tendinitis)

Tendonitis is a condition where the connective tissues between your muscles and bones (tendons) become inflamed. Often caused by repetitive activities or overuse injuries, tendonitis can be painful and limits movement. It commonly occurs in your elbow, knee, shoulder, hip, Achilles tendon, and base of your thumb. If you have tendonitis, you’ll typically feel pain and soreness around your affected joint, usually near where the tendon attaches to the bone. The condition can be either acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term), depending on the severity of the overuse and whether rest and proper treatment are provided. Treatment usually involves rest, avoiding strenuous activities, and allowing the tendons to heal.

Achilles Tendon Rupture

An Achilles tendon rupture is a traumatic injury where the thick band of tissue connecting your calf muscle to your heel bone partially or completely tears. The Achilles tendon is built to handle a lot of stress, but it can rupture under extreme stress—like during a sudden start or stop or if you fall. The classic sign of a ruptured Achilles tendon is feeling (and sometimes hearing) a pop or snap at the back of your ankle. Many people mistakenly think something has hit them, but they’re actually feeling the tendon snap. Other common symptoms include sudden sharp pain, weakness in the affected leg, inability to push off the ground, swelling, and bruising. Without proper treatment, an Achilles tendon rupture may not heal properly, increasing the risk of rupturing it again. Treatment may involve physical examination, imaging tests such as ultrasound or MRI to determine the extent of the tear, and either conservative treatment with rest and bracing or surgical repair depending on the severity.

Keeping Your Tendons Healthy

Maintaining healthy tendons requires a proactive approach that includes proper movement patterns, gradual training progression, and adequate rest. Here are key strategies for tendon health:

- Warm up before physical activity to increase blood flow and prepare tissues for stress

- Gradually increase the intensity and duration of physical activity rather than making sudden changes

- Incorporate strength training to build muscle and tendon resilience

- Use proper form during exercise to minimize abnormal stress on tendons

- Allow adequate rest between intense activities to prevent overuse injuries

- Stretch regularly to maintain flexibility and reduce tension

- Stay hydrated and maintain good nutrition, including adequate protein intake

- Ice sore areas after activity to reduce inflammation

- Seek medical attention early if you experience persistent tendon pain

Diagnosis of Tendon Problems

When you experience tendon pain or suspect an injury, healthcare providers use several diagnostic methods to assess the problem. A physical examination typically includes checking your ability to move the affected area in various directions and observing how you react to pressure on the area. Providers will often feel for specific signs, such as a gap in the tendon that suggests it’s torn. Imaging tests provide more detailed information about the tendon’s condition. Ultrasound can visualize tendon structure and identify tears or inflammation. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) provides detailed images that help determine the extent of a tear or injury. These diagnostic tools help healthcare providers develop an appropriate treatment plan tailored to the specific tendon injury.

Treatment Options for Tendon Injuries

Treatment for tendon injuries depends on the type and severity of the injury. For minor tendonitis and inflammation, conservative treatment is often effective, including rest, ice application, compression, and elevation (RICE protocol). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) may reduce pain and swelling. Physical therapy exercises can help strengthen surrounding muscles and improve flexibility. For more severe injuries like Achilles tendon ruptures, treatment may require immobilization with a brace or cast, followed by physical therapy. Many severe tendon ruptures require surgical repair to properly heal and restore full function. Recovery times vary depending on the severity of the injury and the treatment approach, but patience and adherence to rehabilitation protocols are essential for optimal healing.

Frequently Asked Questions About Tendons

Q: What is the difference between tendons and ligaments?

Tendons are connective tissues that attach muscles to bones, transmitting muscle force to create movement. Ligaments, conversely, are tough fibrous bands of connective tissue that connect bones to other bones and help hold important body structures in place. While both are strong connective tissues, they serve different purposes in the musculoskeletal system.

Q: Can tendons heal on their own?

Minor tendon injuries often heal with conservative treatment including rest and activity modification. However, complete tendon ruptures, particularly in critical tendons like the Achilles, frequently require surgical intervention for optimal healing. The body’s ability to repair tendon damage is limited by the tissue’s relatively poor blood supply in some areas, which slows the healing process.

Q: How long does it take for a tendon injury to heal?

Healing time varies significantly depending on the severity of the injury. Minor tendonitis may improve within days to weeks with rest. Partial tears might require several weeks to months of rehabilitation. Complete ruptures requiring surgery typically involve several months of recovery, with return to full activity often taking six months or longer.

Q: Are there activities that put tendons at higher risk?

Repetitive activities, sudden increases in activity intensity, poor technique during exercise, and activities involving sudden acceleration or deceleration put tendons at higher risk for injury. Athletes, manual laborers, and people who perform repetitive motions are particularly susceptible to tendon injuries.

Q: Can I prevent tendon injuries?

While you cannot completely prevent tendon injuries, you can significantly reduce your risk by warming up properly, progressing gradually with new activities, maintaining good flexibility, using proper technique, and allowing adequate recovery time between intense activities.

References

- Tendon | Description & Function — Britannica. 2024. https://www.britannica.com/science/tendon

- What Is the Achilles Tendon? — Cleveland Clinic. 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/achilles-tendon-calcaneal-tendon

- Anatomy of the Hand & Wrist: Bones, Muscles & Ligaments — Cleveland Clinic. 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/25060-anatomy-of-the-hand-and-wrist

- Rotator Cuff: Muscles, Tendons, Function & Anatomy — Cleveland Clinic. 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/rotator-cuff

- Achilles Tendon Rupture: What Is It, Symptoms & Treatment — Cleveland Clinic. 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21703-achilles-tendon-rupture

- Tendonitis: Symptoms, Causes & Treatment — Cleveland Clinic. 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/10919-tendonitis

- Ligament: What It Is, Anatomy & Function — Cleveland Clinic. 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21604-ligament

Read full bio of medha deb